The Scottish master of the spy game

Before being brutally hacked to death aged 36, Alexander Burnes – one of the greatest spies Scotland has ever produced – lived an extraordinary life.

‘The Great Game’ – even now, nearly two centuries after Britain and Russia jostled for influence at the roof of the world, these three words are perfumed with an almost intoxicating aroma of romance.

The stakes were almost as high as the mountains in which the great game was played: who would control Afghanistan and what should be the proper limits of British India?

Advocates of a ‘forward policy’ for Britain feared Russian encroachment upon British interests in the Hindu Kush. Hawks in London feared the whole panoply of Britain’s Indian possessions might be threatened,

and so securing Afghanistan as a zone of British interest was considered a matter of pressing importance.

It was in this arena that Alexander Burnes, thrived and made his name. Soldier, spy, diplomat, explorer, adventurer, freemason, keeper of an Afghan harem; if his life sounds as though it might have been torn from the pages of Rudyard Kipling or George MacDonald Fraser that is only appropriate.

His real-life story, after all, was a hefty inspiration for their fictional works. He appears in MacDonald Fraser’s Flashman novels and he largely inspired Kipling’s The Man Who Would be King.

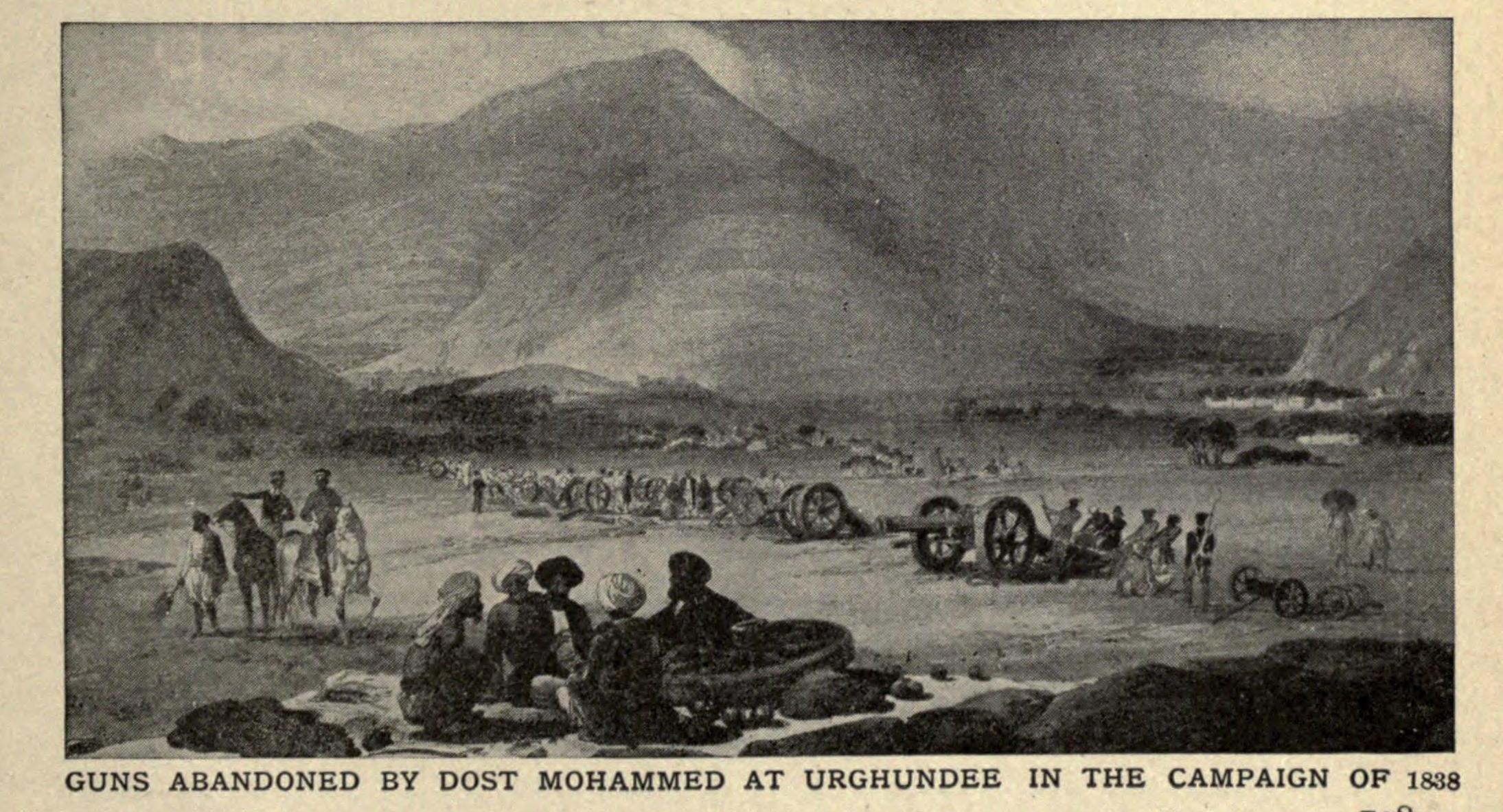

Despite Burnes’ suggesting an alliance with the Emir of Afghanistan, Dost Mohammed, the British sent troops to overthrow him in 1938

Burnes, a great-nephew of national poet Robert Burns, was born in Montrose in 1805. Upon leaving school, he secured a position with the East India Company. This was, in Sir Walter Scott’s words, ‘the corn chest for Scotland where we poor gentry must send our youngest sons’.

In time, he would become Britain’s leading authority on Afghan affairs and find himself at the centre of great, and grim, drama.

Burnes’ is a rich tale that, while amply stuffed with imperial exoticism, also has a resonance today. After all, in the Hindu Kush, as William Faulkner put it in a different context, ‘the past is never dead. It’s not even past.’ The ghosts of empire still linger in those forbidding mountains.

The years since 9/11 have allowed us to hear their voices once again as, for a third time, British troops have been deployed to Afghanistan to pacify a reluctant country.

If Afghanistan has a reputation as a graveyard of empires, it is one that has been well-earned. Britain and Russia learnt the limits of outside infl uence in Afghanistan in the nineteenth century, though this was a lesson the Russians declined to digest in advance of their failed invasion in 1979.

Few have understood the country better than Burnes, a polymath who was a geographer, statistician and linguist as well as an intelligence officer, and whose life occasionally reads as a kind of Victorian Boys’ Own adventure.

In 1831 Burnes, who had a good working knowledge of North-West India and the surrounding area, was dispatched to Afghanistan.

Over the following years he surveyed the route through Kabul to Bukhara, travelling in disguise, surveyed the Indus river while delivering a gift of horses from William IV to Maharaja Ranjit Singh, and roamed across the Hindu Kush to the Uzbek city of Bukhara and on to Iran.

When Burnes’ account of his travels was published in 1834, it was the first detailed picture of the region and was an instant bestseller, earning him the-then huge sum of £800. Fêted, he was elected a fellow of the Royal Society and Royal Geographical Society and admitted to the Athanaeum Club without a ballot, which was almost unprecedented. In 1838 he was knighted by Queen Victoria.

Inspired by the life of Burnes, George MacDonald Fraser’s Flashman in the Great Game was published in 1975

Like other early imperial adventurers, Burnes’ was greatly enamoured with the people. As he navigated the tortuous complexities of Afghan politics, he did so with a sympathy for local tribes and customs that was not always apparent in the later years of imperial expansion.

The question of what to do about Afghanistan was never answered satisfactorily.

Burnes’ argued that London should work with existing local potentates, notably Dost Mohammed, rather than seeking to install a puppet ruler who could be thought more responsive to British interests. London decided otherwise and launched an expedition in 1839 to replace Dost Mohammed.

It was botched from the beginning. In a ‘dodgy dossier’ compiled by the foreign secretary, Lord Palmerston, and given to parliament, it’s clear that Burnes’ despatches from Kabul were presented in a heavily-edited form. References to the lack of any tangible Russian threat were removed; so too was Burnes’ suggestion the British interest lay in an alliance with Dost Mohammed.

He later complained of the ‘pure trickery’ upon which Palmerston’s government made its case for action. Once the decision to install a new ruler in place of Dost Mohammed had been taken, Burnes supported the new policy but ‘not as what was best, but what was best under the circumstances which a series of blunders had produced.’

In contrast to Burnes’ view of the Afghans, one British officer complained that Kabul ‘is beastly dirty and so are the people. They are cunning, avaricious, proud and filthy, notwithstanding the romantic descriptions of Burnes & Co.’ For his part, Dost Mohammed observed that ‘I am but a wooden spoon which can be thrown hither and thither without injury, but the British are a glass which, once broken, cannot be mended.’ That would prove a chillingly prophetic warning.

By September 1840, Burnes worried that the campaign to depose Dost Mohammed and install a puppet ruler was faltering: ‘There is nothing here but downright imbecility,’ he mused. That analysis was a prelude to disaster as Afghan resistance increased. In the early hours of 2 November, 1841, a great crowd of Afghans surrounded Burnes’ house in Kabul.

In the ensuing melee, Burnes fought ferociously, killing six assailants, before, having been promised safe passage to a nearby barracks, Burnes, his young brother Charles and 15 sepoys were hacked to death. His death was a shocking intimation of the weakness of the British position in Afghanistan and a miserable end to a life as fi lled with service as it was with adventure. He was just 36.

Of the many dark days endured by the British Army, few were quite so grim as the retreat from Kabul in 1842. Over 4,500 soldiers took part in the doomed expedition; just one returned alive. It remains the single most catastrophic humiliation in British military history. Even today, notes Craig Murray, the former British ambassador to Uzbekistan who has written Burnes’ biography, he ‘has no grave and no memorial.’ Not in Kabul, nor his native Montrose.

Craig Murray’s biography of Alexander Burnes is published by Birlinn and costs £25.

TAGS