Birds of a feather inspired a modern book

The artwork of an overlooked 19th century ornithologist inspired, and now graces, a modern book on raptors.

It is said that you should never judge a book by its cover. However, it was indeed the half a dozen beautiful early Victorian illustrations of birds of prey perching on the lettering of the book’s title that first attracted me to James Macdonald Lockhart’s debut work, Raptor: A Journey Through Birds.

These images by William MacGillivray are merely a few examples of the extraordinary work of a man who was once deemed Scotland’s greatest field naturalist and an outstanding ornithological artist, yet to this day he remains largely unrecognised.

MacGillivray was born in Aberdeen in 1796, the illegitimate son of a father he never knew, and he grew up on the Island of Harris, raised by his uncle. Inspired by MacGillivray’s approach to field studies whilst working on his book Raptor, Lockhart became absorbed by the brilliance and sensitivity of the artist’s work and in particular by his nature journals.

These were written by MacGillivray on an arduous walk of 838 miles from Aberdeen to London where he visited the British Museum, notes Lockhart. ‘I came to lean heavily on MacGillivray and his methods of studying birds in the field and was often surprised by what I found – perhaps the best example was the sea eagle, a bird that seems sluggish but of course this is not the case.’

William MacGillivray’s 19th century watercolour Golden Eagle with its prey

Lockhart began a similar approach, governed by painstaking observation on his almost spiritual mission to explore each of the UK’s 15 species of raptors.

‘I wanted to find raptors in all parts of the country,’ said Lockhart. ‘MacGillivray’s approach took over the book, adding ballast to my writing. His work is quite exceptional. He studied medicine in Aberdeen and was a trained anatomist. People sent him specimens from all over the country. During the holidays he would walk from Aberdeen to the west to get a boat back to Harris, where his heart always lay.’

In 1830 MacGillivray published his first book but was also working on a major five volume series A History of British Birds. It was during this time that he met the renowned American bird artist J.J. Audubon in Edinburgh and the two men found much in common and became close friends.

Audubon was working on the accompanying text to his illustrated, The Birds of America, and asked MacGillivray to help him edit and correct his shaky English, as well as add scientific detail.

Although Audubon always recognised the incredible artistic skills of his friend and helped give him the confidence to pursue his own painting, Audubon’s work eventually began to overshadow MacGillivray’s. Lockhart, however, describes the pair as an ‘ornithological dream team.’

MacGillivray’s largely untold story runs like a silver thread through Lockhart’s movingly poetic prose in Raptor, but for this reader, the discovery that the author Lockhart is the great-grandson of another outstanding and revered Scots naturalist, photographer and folklorist Seton Gordon, is fascinating.

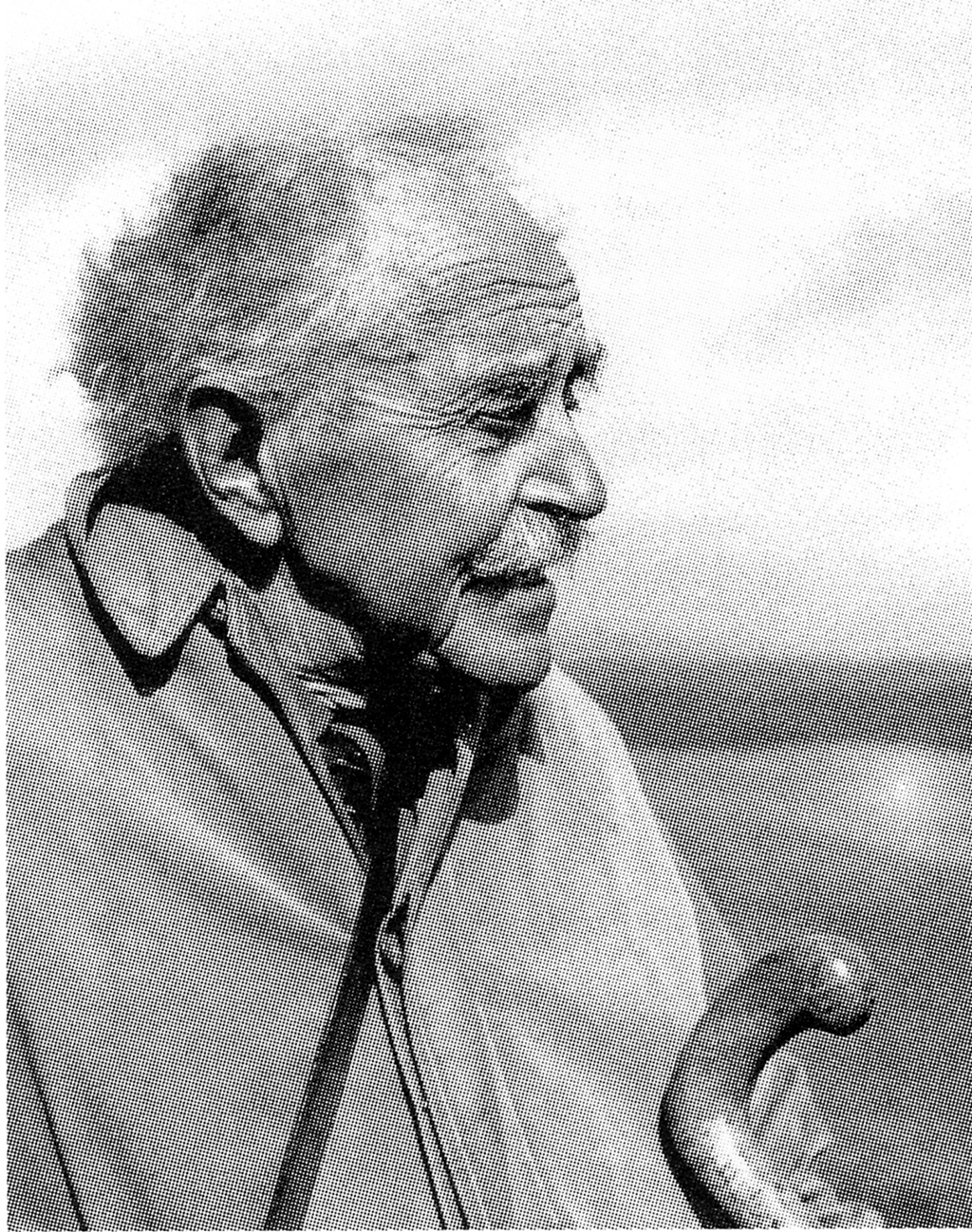

Lockhart’s great-grandfather, the naturalist and photographer Seton Gordon

The prolific author-naturalist Denys Watkins Pitchford – better known as BB – wrote of Gordon: ‘No living writer can capture the spirit of the remote Highlands of Scotland as well as Seton Gordon. There can be few hills and glens where he has not walked and no lochs or river he has not seen, however remote. His writing has a subtle charm which conjures up, in a wonderfully vivid way, the atmosphere of the far northern land, and with his keen sensitivity he links the all-seeing eye of the naturalist which notes the flight of the eagle and ptarmigan, and the wildfowl on the lonely shores.’

Gordon died in 1977 at the age of 90, and although I never met him, his many books were a constant inspiration to my own nature writing, in particular his Days with the Golden Eagle, Highland Days and Hebridean Memories.

He wrote 27 books in total. It is surprising to reread them and discover that most remain blissfully timeless, as fresh as they ever were.

Seton Gordon was renowned as the golden eagle man and many of the eyries and remote locations he described still retain the ancestors of the very birds he knew and loved. He was a pioneer, a true Highland gentleman who strode across the hills in his tattered kilt speaking on the same level to people whether they were an earl or a shepherd.

Like MacGillivray, his field knowledge was extensive but his colourful stories and shrewd observations, leached to an eagerly growing public as he lured them to view mammals and birds through the vignette of a telescope rather than at the end of a gun, were largely unheard of at the time.

For Lockhart, following in the footsteps of two such great naturalists must have seemed weighty indeed. He describes it as: ‘A long journey south, clambering down the tall spiny island, which is as vast and wondrous to me as any galaxy.’

Gordon was a brilliant nature photographer, particularly given that the equipment of the time was cumbersome and unwieldy and had to be carted miles across impossible terrain to where he set up his hides. Thought to be the first person to photograph snow buntings and whooper swans on their nests, Gordon’s famous image of a greenshank and its mate changing over during incubation was brilliantly captured, a poignant tribute to this intensely shy wader that frequents the wildest environments during the brief breeding season.

A golden eagle perched on its eyrie, photographed by Seton Gordon in 1920

‘I grew up surrounded by my great-grandfather’s black and white photographs: greenshanks, golden eagles, gannets and dotterels all peering down at me from their teak frames,’ writes Lockhart. ‘I liked to take them off the wall, wipe the dust from the glass and then turn the pictures over to read the captions he wrote on the back. Whenever I move house the fi rst pictures I hang are two small photographs; one of a jackdaw pair – black and pewter – the other of a hooded crow in a sleeveless silver waistcoat.’

Though Lockhart never knew his great-grandfather, his own love of natural history and growing knowledge on the subject has been greatly driven by his work and the stories his grandmother – Gordon’s daughter Catriona – revealed about him.

Whilst Seton Gordon received the accolades and notoriety that he richly deserved, not so William MacGillivray. He never had enough money to finance the production of his brilliant artwork in his own volumes, although many of his works were published subsequently.

Seton Gordon’s famous image of a greenshank and its mate

He received awards and became Regius Professor of Natural History at Aberdeen, but many of his outstanding paintings were never given the recognition they deserved.

After MacGillivray’s death at the age of 56, Queen Victoria had his Natural History of Deeside published, an accolade indeed. In comparison, the works by the American Audubon sell for millions of pounds and are still seen and reproduced all over the world to this day. Was it merely that MacGillivray was in the wrong place at the wrong time?

‘MacGillivray’s writing, for me is a way of seeing,’ explains Lockhart. ‘He misses nothing. And he misses nothing out in his descriptions of the birds. Sometimes I just want to hand everything – how to find the birds, identify them, how to write about them – over to him.’

Lockhart seems shy and full of self-doubt, yet he has put William MacGillivray firmly back on the ornithological map. His great-grandfather, Seton Gordon, would surely revel in his great-grandson’s glorious celebration of the rapacious birds of the British Isles in this stunning book.

Through Birds – James Macdonald Lockhart, published by Fourth Estate, £16.99

TAGS