Prime Ministers and their relationship with a dram

Tales of late-night whisky-drinking are very much part of the mythology of British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher (PM: 1979-1990), but what is perhaps less well-known is that many of her political forebears long had a significant relationship with the amber fluid.

In fact, whisky has played a crucial part in the economic life of Britain and – by extension – in its political life for centuries. Most of our greatest Premiers have debated excise duties, tinkered with licensing laws and hours, and ruled on export regulations affecting the whisky industry. And some of them – like Mrs T – have personally benefited from a wee dram in their efforts to cope with the demands of Britain’s top job.

Take William Pitt the Younger (PM: 1783-1801 and 1804-1806), for instance. He became Prime Minister at the tender age of 24 and found himself faced with an enormous National Debt of £243 million (due largely to the American War of Independence 1775-1783).

To replenish the coffers, Pitt sought to raise taxes by any means possible. His Wash Act (of 1784 – amended 1786) divided Scotland into Highland and Lowland areas. It was deemed that North of the line producers could make only malts (whisky made from malted barley) and they would be taxed on the capacity of their whisky stills. South of the line, in the Lowlands and England, on the other hand, producers would be allowed to make whisky from any type of grain, and it would be the fermented ‘wash’ itself (the liquid from which the whisky was distilled) that was taxed (at a rate per gallon).

British Prime Ministers have had a long relationship with whisky

This ‘Highland Line,’ as it became known, was drawn as a means of lowering duties on whisky in the Lowlands and England to stimulate more legal distilling there and ultimately to raise funds for the government.

Pitt himself was a notorious heavy drinker who favoured port and became known as a ‘three-bottle man’ because, it was said, that he could drink three (350mml) bottles a day. Suffering from chronic ill-health he was advised to drink whisky by his doctors and developed a real taste for the stuff. Unfortunately, such ‘medicine’ on top of his regular intake of alcohol caused him to suffer even more greatly from gout and biliousness and he eventually died (probably from a duodenal ulcer) at the still relatively young age of 46!

The next significant moment in the political history of whisky came in 1823 under the Premiership of Lord Liverpool (Robert Banks Jenkinson PM:1812-1827). Whether Liverpool himself particularly enjoyed whisky is not known, but his dinner parties were deemed to be ‘sober’ occasions, and his character has been described as ‘careful’ if not ‘mediocre,’ so perhaps it is unlikely.

Nevertheless, Liverpool was to grant a boon to whisky producers in the last years of his office. During the early 1820s, the taxes payable on whisky had increased to such an extent that it was almost impossible for Scottish producers to make a profit legally and thousands of illegal stills were in operation. To attempt to rectify these problems, the Excise Act (1823) sanctioned the distilling of whisky for a licence fee of £10 and a set payment per gallon of proof spirit.

In effect, this meant that the rate of duty payable on whisky by the producers had been dramatically cut, large-scale production now became viable, and illicit stills were all but wiped out.

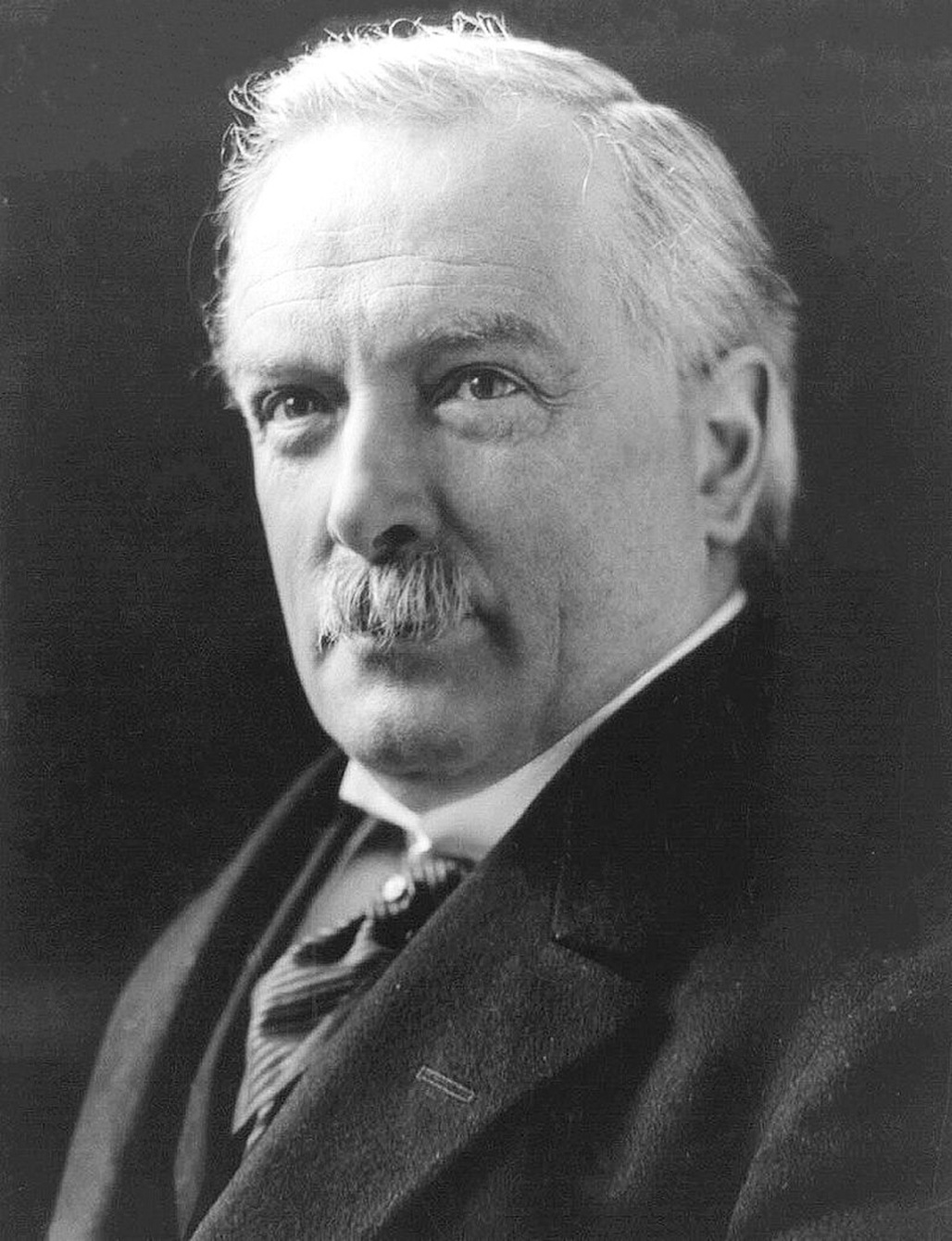

Prime Minister David Lloyd George

The nineteenth century saw repeated political moves to tighten and relax the licensing laws – legislation which affected how alcohol of all kinds was consumed in Britain. But during the First World War, whisky was again singled out for particular attention. Prime Minister David Lloyd George (PM: 1916-1922) has been accused of trying to break the whisky industry. He was, in fact, a tee-totaller and it is possible that his personal renunciation of alcohol affected his policies to some degree.

Certainly, it was on his watch that the Immature Spirits Restriction Act of 1915 was passed. This extended the amount of time for which whisky had to be aged in oak casks to two (and later to three) years. These changes coupled with restrictions in licensing hours during World War One forced many whisky distilleries to close, although ironically the longer maturation period had the effect of improving the remaining product in the long run.

Our Prime Minister during the Second World War, had rather a different attitude to whisky both professionally and personally. Winston Churchill (PM: 1940-1945 and 1950-1955) saw the potential for whisky to make Britain money in the early years of the War, and purposefully diverted shiploads of Scotch to America in part payment for the war materials that Britain badly needed. As the war progressed, however, the national shortage of barley meant that many Scottish distilleries were forced to close and the ruination of the industry seemed likely.

In January 1945, however, Churchill thankfully came to its rescue, making limited supplies of grain available for whisky distilling with a view to replacing stocks and also to supplying America and other foreign markets into the future. There was a spectacular expansion in output and export of whisky in the 1950s when Churchill took office as Prime Minister for the second time. At this time, American businesses invested heavily in Scotland buying whisky stocks, warehouses, bottling plants and brands and many old distilleries were refurbished and new ones acquired.

Sir Winston Churchill

Churchill himself had disdained whisky as a young man preferring brandy. But as a young army officer fighting in Afghanistan in 1897 he found the combination of whisky and water the most appealing of drinks on offer to the military. He remarked that once he ‘got the knack of it, the very repulsion from the flavour developed an attraction of its own.’

There are many tales of his later fondness for whisky including the one about his travels to South Africa as a war correspondent in 1899 when he apparently took 18 bottles of a ten-year old Scotch in his luggage! Churchill’s favourite whisky was Johnnie Walker Red Label which was to be found in a glass mixed with water by his side all day long. He was no drunkard, however, and used the tipple as a mouthwash rather than a drink according to his Private Secretary Jock Colville!

In the final decades of the twentieth century, whisky sales saw a severe downturn. This was partly due to the over-production of whisky in the 1970s when, some say, the industry had overinvested in bringing old distilleries back into use.

As we know, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, was a great lover of whisky. Although she had been brought up as a strict Methodist – and therefore without exposure to alcohol – she had been encouraged to drink by her husband Denis, and was often, it is said, to be found quaffing a blended whisky (usually Bell’s) and soda (without ice) in the Bar of the Commons. Thatcher’s drink of choice was partly borne out of her desire to keep control of her weight; she believed whisky and soda to be less fattening than gin and tonic.

Unfortunately Thatcher’s personal predilections did little for the whisky industry. She did sanction The Liquor Licensing Act of 1985, which brought in less restrictive licensing hours with a view to increasing revenue from alcohol sales. But National consumption of whisky did not increase as a result of this.

American president Donald Trump received a bottle of whisky from Theresa May

Current Prime Minister Theresa May’s feelings about whisky are not common knowledge but, perhaps her gift to Donald Trump when she met him at the White House in January 2017 speaks for itself. She presented him with an engraved Scottish quaich or whisky cup (a token of hospitality and a symbol of kinship) as testimony to his Scottish roots.

The whisky industry is booming and the role of the drink in our national politics is definitely far from over.

TAGS