The Scot who was off the strait and narrow

The temptingly wide strip of water was a terrible place to bring a ship in a gale, despite the arrival of a mystery Scot as protector.

Only discovered by the British explorer George Bass a few decades before the Cataraqui went down in 1845 – still considered Australia’s worst peacetime disaster – the fact that the Bass Strait existed between the Australian mainland and its island state of Tasmania ‘should never have been made public’.

That was the opinion of Bern Cuthbertson, the veteran seaman who re-enacted the 1798 Bass and Flinders circumnavigation of Tasmania in a longboat and told me, ‘It would’ve been far safer in those days for ships heading for Sydney to go around Tasmania.’

The worst offender in this ‘shipping graveyard’ was King Island, whose ‘unremarkable, low, rocky and treacherous’ coast would, according to Commander J. Stokes R.N. in 1838, claim 700 lives in an astonishing 57 shipwrecks.

Ketches, barques, brigs, cutters, schooners – in fact ships of all sizes and shape which approached the island from west or east – would encounter reefs that in some places extended four miles beyond the shores of King Island itself.

Christopher William Finlay, the captain of the emigrant ship Cataraqui, would have known it was madness sailing into a place like this in the dark with hundreds of passengers in August 1845. So, why did he?

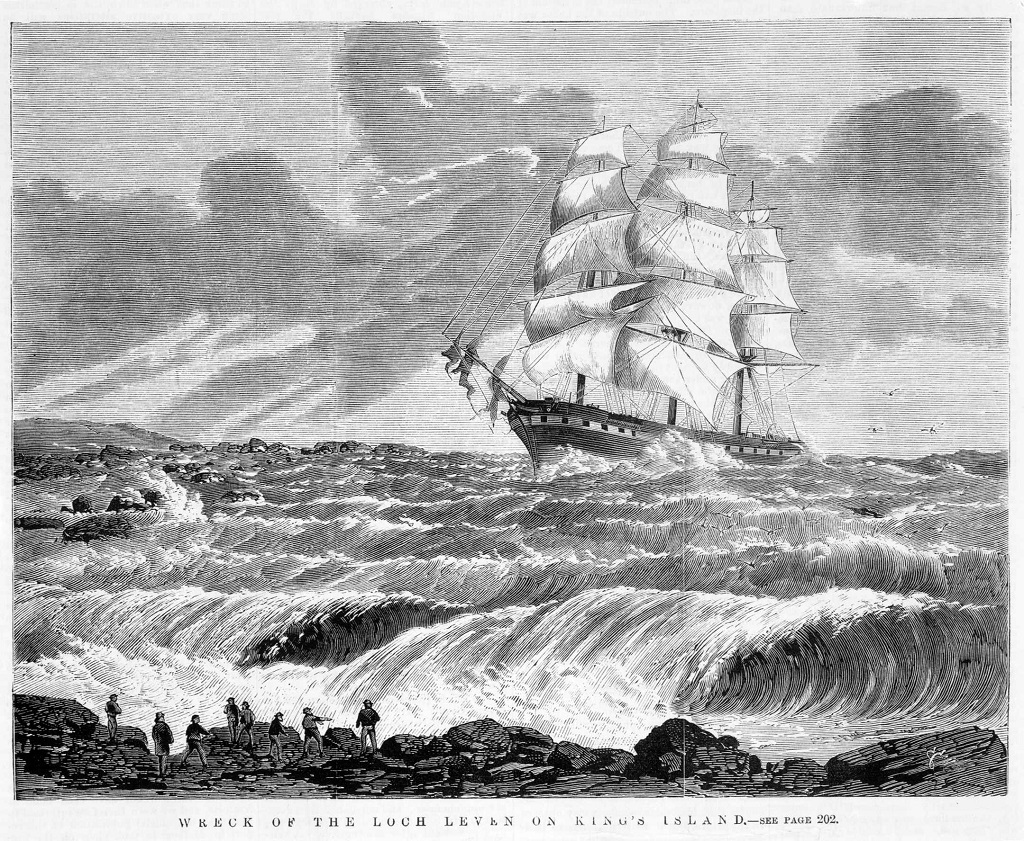

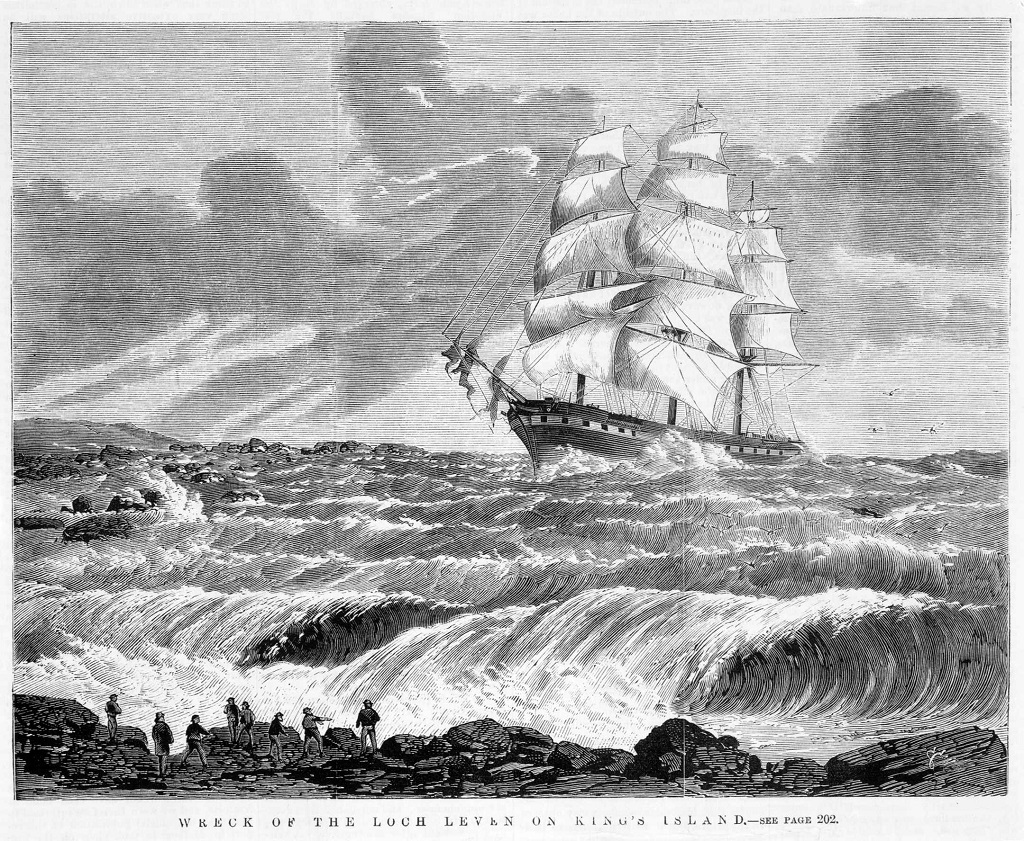

The wreck of the Loch Leven on King Island in 1871 (Image: State Library of Victoria)

The ship left Liverpool bound for Melbourne on 20 April that year with 41 crew and 369 emigrants – men, women and children. The voyage had been largely uneventful, apart from the loss of one crew member overboard, five babies born and six others dying. But hardly anyone on board would survive what was about to

happen as the ship approached King Island in a storm.

Finlay made the ‘correct and seamanlike decision’, or started to, when ‘he hove to, intending to ride out the storm until dawn’, wrote Chris Halls in Australia’s Worst Shipwrecks.

But one of the surgeons on board, Charles Carpenter, had been nagging Finlay about how long the journey was taking, warning that disease might break out. Carpenter was also due a bounty for each ‘healthy immigrant landed’, so his concern was not necessarily medical.

Instead of confining Carpenter to his cabin, Captain Finlay allowed him to bully him into going on. It was 3am. An hour later the ship ploughed into a reef 100 yards off the south-western end of King Island. Although it took 30 hours for the ship to break up completely, only nine men would make it alive to shore.

The eight sailors and one immigrant, Solomon Brown, had nothing but a few items – ‘a case of preserved fowl, a small bottle of brandy, a cask of water and one sodden blanket’ – that had been washed ashore with them.

Scared to light a fire as they believed they were on the Australian mainland, which they assumed was inhabited by cannibals, the cold, wet, hungry men survived the night.

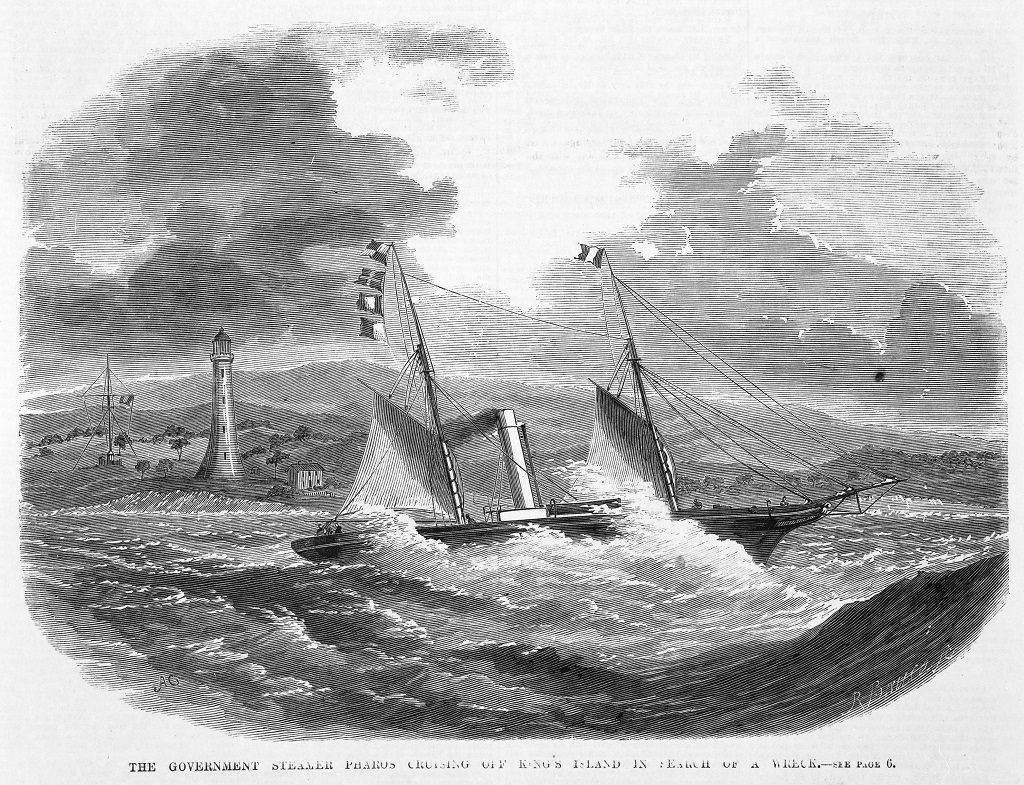

The Tasmanian government steamer Pharos searching for the foundered schooner Mary Ann off King Island in 1878 (Image: State Library of Victoria)

None was prepared for the sight that met their eyes the next morning, when a figure approached them out of smoke on the northern horizon. Assuming it was aborigines with spears, they hid in the bushes; but it was Scotsman David

Howie. After seeing a body wash up near his camp, he and his four sealing partners were scouring the island for survivors.

After giving them food, dry clothes, and building a windbreak – which undoubtedly saved their lives – he disappeared. Howie had promised to return the next day with shovels to begin the burials, until the cutter Midge arrived five weeks later and took the nine bedraggled castaways to Melbourne. But who was this man, and had he really been their saviour?

Howie was born in Ceres, a village seven miles outside of St Andrews in Fife on November 1, 1815, the son of stonemason John Howie and Katharine Straitfurd.

One of the Howies is believed to have carved the Provost statue in its main street. A coach would leave Ceres each day and connect with the ferry on the Firth of Forth, and we know Howie boarded it at least once because it was stealing in Edinburgh that got him transported to Tasmania (or Van Diemen’s Land, as it was called then) in 1837.

After serving his seven-year sentence, Howie began trading around Bass Strait. Other ex-convicts also marauded around the islands, one man taking two aboriginal women as his ‘wives’ to King Island, where he left them to hunt kangaroos and seals.

The trade was lucrative and Howie did not like sharing it. He received £1 for every kangaroo skin and once shipped hundreds of tons of guano he found 1.2 metres (4ft) deep on one island to Launceston, in north-ern Tasmania, at £50 (over £4,000 today) per ton.

In 1846 he wrote telling Tasmania’s lieutenant-governor how many people he had rescued and asked to be made the island’s ‘policeman’. Astonishingly, despite once being charged with neglect of duty for being asleep at the Post Office, the lieutenant-governor agreed; Howie couldn’t believe his luck. One newspaper notice printed at the behest of the new Special Constable for King Island began: Notice to Sealers, Hunters and Others.

The undersigned hereby cautions the public and William Proctor of Circular Head in particular against trespassing in any way.

In 1847 Howie told the authorities that rumours were rife regarding bonfires lit on the hills to lure ships ashore. ‘Once the ships are in trouble these rogues go on board and plunder them,’ he said.

The local newspaper, The Examiner, found his claim difficult to prove but 100 years later, on October 20, 1936, it confirmed its suspicions, saying: ‘Howie was a wrecker.’ So, was Howie not only spreading the stories as a protection racket but deliberately lighting fires too?

Ship captains were surprised to hear Howie opposing the building of a lighthouse because ‘the land was low…the lagoons causing heavy mists’. He said having someone living on King Island who could rescue people from the shipwrecks was better than building a lighthouse. It was also cheaper, which tempted the government.

But going for the ‘Howie option’ was to prove a costly mistake: by the time a lighthouse was built in 1861 at Cape Wickham, on the island’s northern tip, nine more ships had been wrecked.

The tombstone of Mary Bogue (wife of Capt Howie) also Black Mogg (servant) and David Howie Bogue (baby) (1897 photo: Tasmanian Archive & Heritage Office)

By 1861 Howie the wrecker was dead, but it is deeply ironic that the shipwrecks continued because many sea captains mistakenly mistook the new lighthouse for the Cape Otway Lighthouse on the Victorian coast, 56 miles north, causing them to sail south of it and plough straight into King Island, resulting in even more ships, such as the Netherby (1866) and Loch Leven (1871), being wrecked.

But Howie would not live to know this. For the 13 years he had been the island’s official protector he lived on King Island with his wife, aborigine Mary Bogue, and they had a child, David Howie Bogue.

Both mother and son died with another aboriginal woman in 1851 when their boat, overloaded with potatoes, overturned near its mooring in Stanley, on Tasmania’s north-west coast.

After a distraught Howie left for the gold rush on the Australian mainland, a letter arrived in Hobart from his brother John at 75 Leonard St, Edinburgh saying that his family was anxious for news of him. An official had told them of his new position on King Island, but by now Howie would have been far away across Bass Strait in the mountains of Victoria scrabbling in the mud for nuggets.

In 1853 Howie, by now back in Stanley, married Jane Wilson and they had three daughters.

All seems to have gone well until May 1859 when Howie was repairing a dinghy near Stanley and gave two men a ride in it to save them having to walk through bushland. Although an oar was washed up, none of them was ever seen again.

Perhaps it was fitting in the end that a this shipwrecker from Fife, who was said to have profited from the death at sea of hundreds of innocent sailors, was himself lost at sea.

TAGS