Scotland’s young writing talent – who died aged 8

In 1811, eight-year-old Marjory Fleming contracted meningitis and died. She was quietly buried without ceremony in a simple grave in Fife.

However, she left behind her three journals, a book of poems and some letters which, fifty years later, had the Victorian literati hailing her as a child prodigy, sold in their thousands and ensured that her name was forever etched into the public imagination.

Born in Kirkcaldy, Fife, Marjory was the third child of accountant James Fleming and his wife Isabella. Clever, energetic and short-tempered, Marjory was something of a handful, so when her mother became pregnant again she was sent to stay with her relatives in Edinburgh, the Keiths. She was only five years old.

Marjory was tutored by her twenty-year-old cousin, Isabella, who encouraged her young charge to keep a journal in which to practice her penmanship. Marjory spent three years in Edinburgh, during which time she became very fond of ‘Isa’, ‘the darling of my heart’.

Marjory proved to be an extremely able student and filled three journals which, alongside writing exercises, contain musings on a range of topics including history, religion and even love (‘Yesterday a marrade man named Mr John Balfour Esg offered to kiss me, & offered to marry me though the man was espused, & his wife was present & said he must ask her permission’), as well as the more trivial and prosaic.

Marjory also wrote poems, including an epic about the life of Mary, Queen of Scots.

In 1811 Marjory returned to Kirkcaldy at the request of her mother. Sadly, soon after returning home she succumbed to a measles epidemic that was ravaging the town and, on 21 December – a month before her ninth birthday – she died. The recorded cause of death was ‘water on the brain’, which is now believed to have been meningitis, caused by her measles.

The grave of Marjory Fleming

Her journals, poems and some letters were saved by her family as a relic of her life.

Marjory’s writings remained hidden away until 1847, when they were ‘discovered’ by the writer, HB Farnie. He published a short article in the Fife Herald, Pet Marjorie: A Story of Child Life Fifty Years Ago which was reprinted as a pamphlet in 1858.

In 1863 Dr John Brown published Pet Marjorie, which interspersed Marjory’s writing with a heavy dose of sentimentality, written in a sugary prose intended, successfully, to tug at the heartstrings of Victorian society. He claimed that Marjory had been close friends with Sir Walter Scott, who had described her as ‘the most extraordinary creature I have ever met with’.

According to Brown, ‘Sir Walter was in that house almost every day, and had a key… “Marjorie! Marjorie!” shouted her friend, “where are ye, my bonnie wee croodlin doo?”’ However, the sole evidence for Scott’s connection to

Fleming is in a letter written by her sister to Brown some fifty years after her death, and as such it may well be an exaggeration, if not a complete fabrication.

Whilst Sir Walter Scott’s affection for Marjory Fleming is debatable, there is no doubting the praise heaped onto her by other literary heavyweights. Robert Louis Stevenson called her ‘one of the noblest works of God’, whilst Leslie Stephen, the father of Virginia Woolf, described her as ‘a loving and charming child genius’.

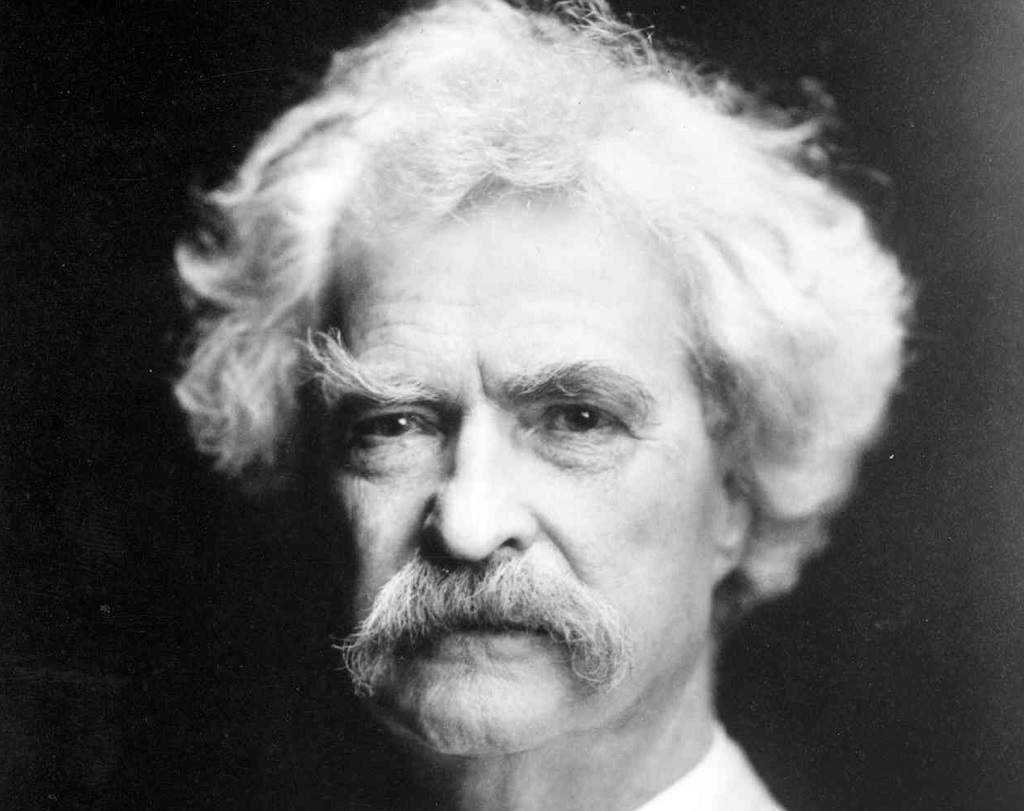

The American author, Mark Twain, also eulogised Marjory’s prodigious talent.

Mark Twain

In 1909, the last year of his life and thirteen years after the death of his own daughter (also a gifted young writer who died of meningitis), Twain wrote an essay called Marjory Fleming: The Wonder Child. In it, he referred to her as ‘the world’s child, she was the human race in little… Nothing was entirely beyond her literary jurisdiction; if it had occurred to her that the laws of Rome needed codifying she would have taken a chance at it’.

Pet Marjorie captured the public imagination and its popularity cannot be overstated. Newspapers claimed that one edition of the book had sold ‘fifteen thousand copies’ and that Marjory Fleming’s story had ‘attracted the notice of the Queen’. Fleming’s appeal endured throughout the nineteenth century and beyond: in 1898 she was given an entry in The Dictionary of National Biography, which claimed that ‘No more fascinating infantile author has ever appeared,’ and other versions of Marjory’s writings were published in 1904 and 1934 respectively.

Whilst her admirers recognised a prodigious talent in Marjory’s writing, most conceded that it wasn’t of the same standard as a young Shelley, for example. Either way, it doesn’t explain her lasting popular appeal. Rather it was the way her character shone through in her prose. ‘The personality of hers is, indeed, the real secret of Marjorie Fleming’s assured place in our hearts’, wrote one commentator. Another affectionately described her as a ‘merry, inconsequent babbler’.

This ‘personality’ is on clear view throughout her writing. In one passage the six-year-old Marjory describes a female acquaintance as a ‘horrid fat Simpliton’. In another she feels remorse for calling someone an ‘Impudent Bitch’. She also acknowledges her short temper: ‘I have been more like a little young Devil than a creature… I stamped with my feet and threw my new hat on the ground and was sulky and dreadfully passionate.’ It was this mischievous honesty that produced such an affectionate response from her readers.

The nineteenth century also witnessed a shift in attitudes towards children and childhood, which was being viewed as something to be cherished. It was no longer acceptable for children to work in mines or factories, education was being valued and in the home children were increasingly being allowed to act like children.

At the same time childhood was becoming romanticised in the writings of authors such as JM Barrie (Peter Pan) and Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland). It is in this context, then, that Marjory Fleming reached out to her Victorian audience.

Ultimately, though, it was Marjory’s real life story that resonated most with her audience.

Had she not died so young it is unlikely that her writings would have been revered in quite the same way. Indeed, no sugary language is required to appreciate the tragedy of Marjory’s last few months in Kirkcaldy, desperately pining for her cousin who, for one reason or another, failed to visit and who would never see her again. ‘You have disappointed us all very much especially me in not coming over,’ Marjory wrote to Isa. ‘Every coach I heard I ran to the window but I was always disappointed…’

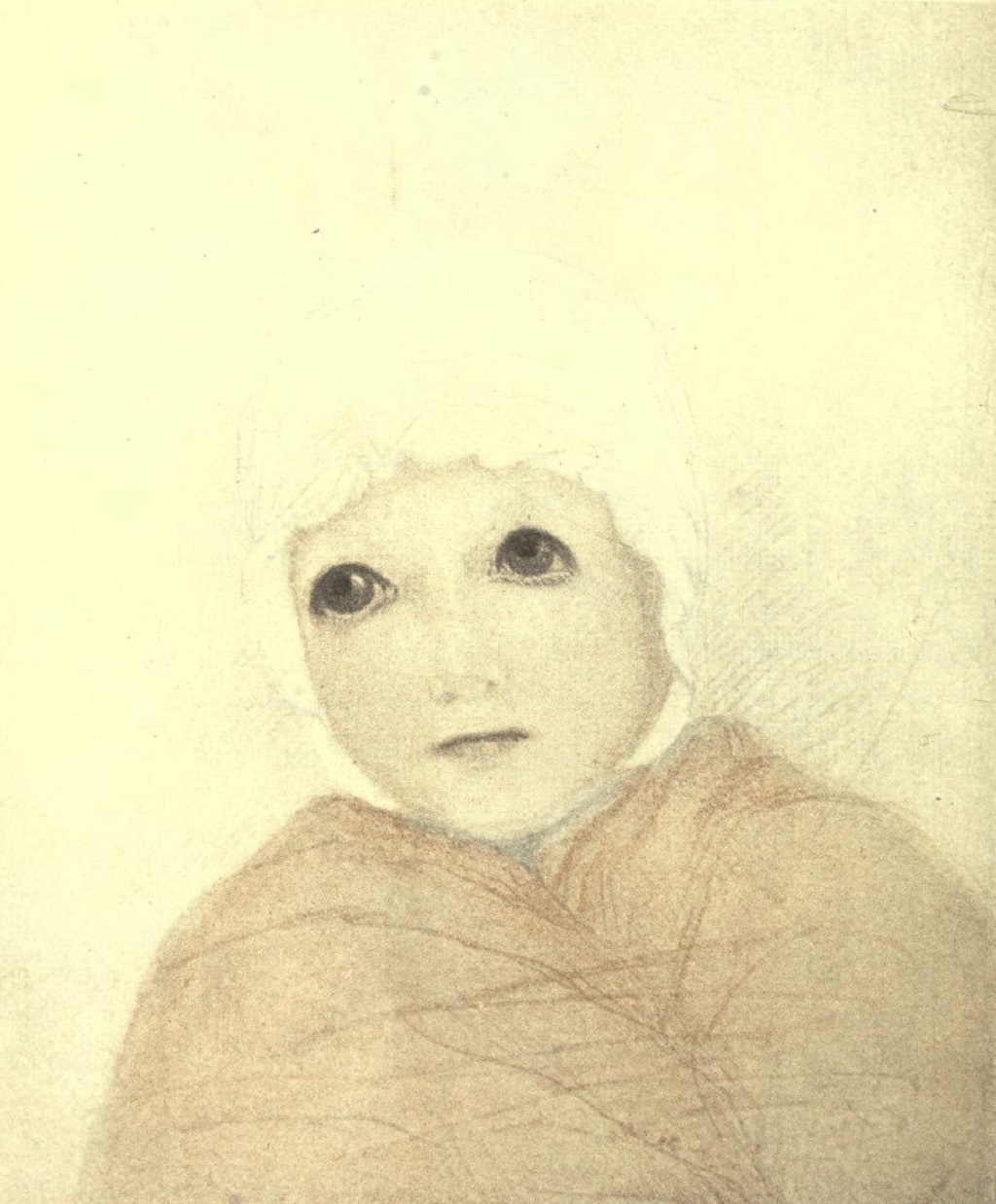

A portrait of Marjory Fleming

A few days before her death, it looked as if Marjory was over the worst of her illness, and would recover. During this brief period she wrote what would be her last poem, her final words, titled To Her Loved Cousin on the Author’s Recovery.

‘Oh! Isa, pain did visit me / I was at the last extremity / How often did I think of you / I wished your graceful form to view / To clasp you in my weak embrace / Indeed I thought I’d run my race…’

Later that night Marjory went to bed and woke in the middle of the night crying ‘my head, my head’. After three days of unbearable suffering she passed away. She was buried in Abbotshall Churchyard, Kirkcaldy.

For Isa, Marjory’s final poem must have been painful to read. Her guilt at not visiting Isa during those final months will have been profound.

However, she may have taken some comfort from the kind words of Marjory’s mother, in a letter written shortly after Marjory’s death: ‘To tell you what your Maidie said of you would fill volumes; for you was the constant theme of her thoughts, and ruler of her actions… The last time she mentioned you was a few hours before all sense save that of suffering was suspended, when she said to Dr Johnstone, “If you will let me out at the New Year, I will be quite contented. I want to purchase a New Year’s gift for Isa Keith with the sixpence you gave me for being patient in the measles; I would like to choose it myself…”.’

Marjory Fleming’s diaries, poems and letters show the buds of a prodigious talent. However, it was the picture of a young, happy girl taken before her time that really captured the public imagination and which has allowed her tragic story to endure for so long.

TAGS