The Dark Room at Perth Art Gallery: The pre-digital age of photography and the Scottish photographers that paved the way

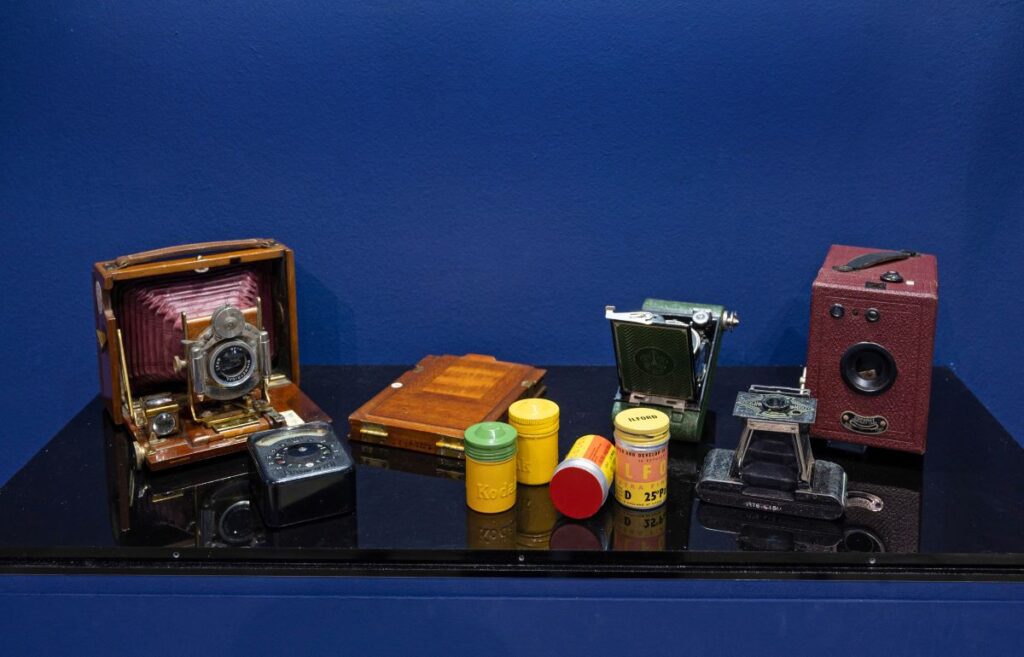

For 150 years before digital photography became commonplace, photographic images were captured by the action of light on chemicals. The materials and processes evolved over time each having their own unique aesthetic. Now an exhibition at Perth Art Gallery will explore the pre-digital age of photography and how different processes have changed the aesthetics of photography over time.

Credit: Julie Howden.

Scottish photographers made significant contributions to the early development of photography, but none more than Robert Adamson and David Octavius Hill.

Widely credited as making photography accepted as an art form in its own right, their pioneering work is known across the world.

Adamson was one of the first professional photographers, setting up in business in Edinburgh in March 1843. Shortly after opening his studio on Calton Hill, he met painter David Octavius Hill and the pair went on to create a famous partnership exploring the possibilities of photography.

Hill trained as an artist at Perth Academy and is best remembered for his use of the calotype process, which deployed a paper negative that allowed the production of multiple print copies.

The calotype was just one of the early photographic processes, and the characteristics of the calotype were very different to the daguerreotype, the rival French process developed by Louis Daguerre and announced in 1839.

David Octavius Hill by Robert Adamson and David Octavius Hill 1843

‘When digital is so easy and the results so good, why would anyone hark back to the days of film?’ Curator Paul Adair said.

‘There is something special about the look of these analogue processes. So many developments have occurred during photography’s long history and each process brought its own particular character.

‘Even at the very beginning of photography you had two competing processes which used entirely different methods to produce a photographic image.

‘The Daguerreotype process devised by Frenchman Louis Daguerre created a direct positive image on a silvered copper plate.

‘Meanwhile in England, Henry Fox Talbot had found a means of sensitising paper to create a negative which could then be placed in contact with a further sensitised sheet to create positive copies.

‘The two processes each had their merits and a very different appearance from one another.

Perth before Tay street was built by Magnus Jackson (1831-1891)

‘There is something wonderful about the physicality of these processes. It’s something you can touch and hold, not just a digital file consisting of ones and zeros.’

The exhibition at Perth Art Gallery takes visitors from these early days and goes on to explore the wide scope of photography with images as diverse as an image of a plaster cast of a Pompeii victim to Alex Ferguson scoring a goal at Perth’s Muirton Park grounds in 1967.

Curator Paul represents the evolving role of the photograph in our everyday lives through a job-lot of snapshots from 1928 to 1960 purchased at auction. Portraying precious family memories, the photographs have a particular poignancy now.

The exhibition also looks at our changing perception of images over time. The unique qualities of analogue images captured by the action of light on chemicals rather than made up of combinations of ones and zeros, have a magic that is being rediscovered by the born-digital generation.

Credit: Julie Howden.

Similar to the increasing popularity of vinyl records, the special aesthetics of analogue photography are being discovered by a younger generation.

Demonstrating that analogue is not dead, the exhibition concludes with the contemporary work of Scottish photographers, including Sophie Gerrard, who continues to favour film over digital and has been capturing the lives of women working in the traditionally male dominated world of agriculture.

The use of lightboxes within the dark and striking upper rotunda, the oldest part of Perth Art Gallery, just reopened to the public, adds drama to the images.

‘I think there is a clear parallel between analogue photography and the appeal of Vinyl records – that tangible object that you can hold and store,’ Paul added.

‘Plus the unique sound quality that may not be technically ‘better’ but has its own appeal perhaps like the grain of a film image.

‘I think it’s not just older photographers who miss the allure of the darkroom – watching the image magically appear under a red safelight – but also the born-digital younger generation who are discovering the joys of film for the first time.’

Read more News stories here.

Subscribe to read the latest issue of Scottish Field.

TAGS