Scotland has been going Dutch since 1066

The issue of migration to Scotland has been much in the news over the past decade with a significant inflow of people coming from the eastern part of the European Union and more recently from Syria.

But while immigration is not a new phenomenon for Scotland, it is perhaps little known that immigrants from Flanders – Flemish people – were one of the most important immigrant groups to Scotland for almost six centuries between 1100-1700.

Medieval Flanders was quite different from the Dutch-language region of Belgium that we know as Flanders today. In the 12th century the principality of Flanders covered much of what is now north-western France, western Belgium and most of the province of Zeeland in the Netherlands.

But since then the borders of Flanders, whose pivotal position between the Atlantic Ocean and the North Sea has made it coveted and therefore vulnerable, have changed frequently under the influence of changing alliances and the intrusion of various armies.

So why did people leave Flanders and come to Scotland?

The first wave came from the Flemish elite; the second were economic migrants seeking to improve their lot; and the final wave was made up of migrants fleeing from religious persecution.

The earliest Flemish people came to Britain with William the Conqueror’s invading force in 1066. They were closely allied with the Normans, not least because William’s wife was the daughter of a count of Flanders. William rewarded these elite Flemish knights for their help with a gift of land in England. So an initial Flemish foothold in England was established.

Some years later, in 1124, David I ascended to the Scottish throne and his wife Maud, who was of Flemish heritage, came up from England with him, accompanied by a retinue of her Flemish kinsmen. Further elite Flemings were brought to Scotland to help subdue the local population and assist in ‘modernising’ the country.

The skills the Flemish brought with them – which included agriculture, architecture and engineering – meant that they contributed to the society they were joining.

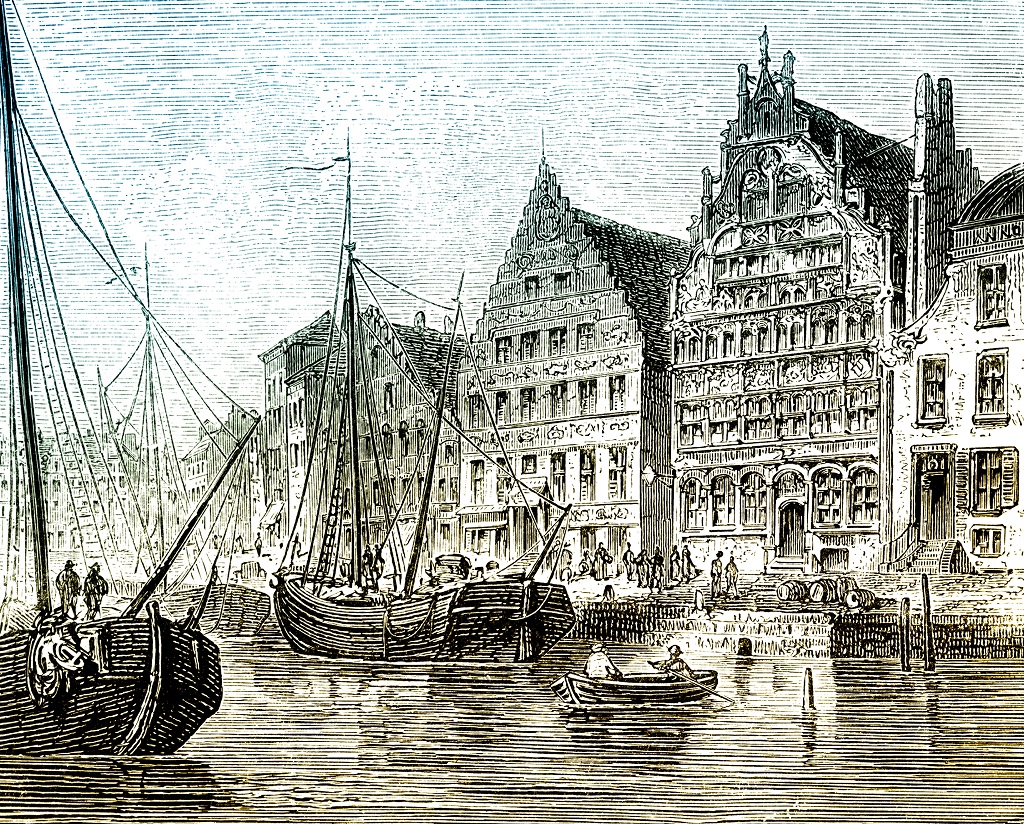

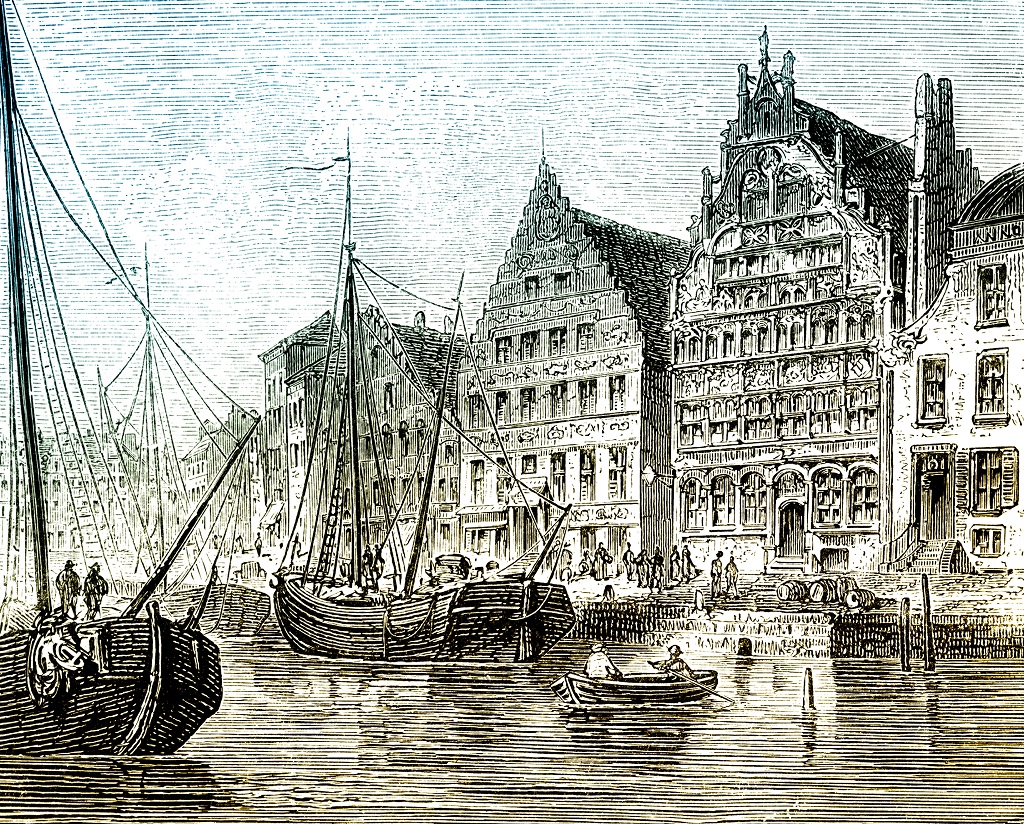

Ghent, now in the Flemish region of Belgium, was one of the largest and richest cities of Northern Europe in the 1300s

The inflow of Flemings continued through the reign of Malcolm IV (1153-65), spurred in 1154 by Henry II’s expulsion of Flemings from England on the grounds that they were encroaching on English trade. The areas of Scotland most associated with the settlement of these elite Flemings were Upper Clydesdale and Moray.

To understand the arrival of the later Flemish economic migrants in Scotland some background is needed.

During the 13th and 14th centuries Flanders was an economic powerhouse driven by a textile industry that supplied luxury woollen goods to much of Europe. The relationship with Scotland was one of mutually beneficial exchange where Scotland’s thriving burghs provided raw wool for the Flemish weaving industry and these exports became an engine for the growth of the Scottish economy.

In return, Flanders exported to Scotland high-end items such as tapestries, munitions, bells, and finished woollen goods. Flemish craftsmen were often brought to Scotland, sometimes temporarily, to fulfil a demand for desirable Flemish items.

The rapid growth of the textile industry led to an increasing call on land for sheep grazing in Flanders and a heavy concentration of weaving, and hence people, in urban areas. The resulting overpopulation forced some people to leave the country. Subsequently, from about the middle of the 14th century, with increasing competition from other producers in Europe, the Flemish textile industry went into decline, causing economic dislocation and unrest among the working people. All of these economic factors again encouraged people to leave Flanders with many heading to Scotland.

This movement was as much a pull as a push, with the Scottish government of the late 16th century recognising the benefit of encouraging Flemish weavers

to settle in Scotland. Acts of Parliament were passed in 1581 and 1587 that provided economic incentives for Flemish weavers to settle in Scotland, where it was hoped they would train local Scots in the art of weaving.

In the 16th and 17th centuries the final phase of Flemish migration took place, and although the numbers of people coming to Scotland were relatively small, they had a profound cultural impact. The root cause of this third wave of migration was religious persecution in the Low Countries, whose Spanish rulers sought to maintain Catholic worship despite the great divide caused by the Protestant Reformation.

When in 1522 Charles V unleashed the Inquisition upon the Protestants in the Low Countries and condemned all heretics to death, it led to further waves of migration from Flanders. Many initially went to England and then on to Scotland, a scenario which was repeated towards the end of the 17th century when Protestant Huguenots fled persecution at the hands of King Louis XIV of France.

Three centuries later it is germane to ask what the Flemish legacy in Scotland has been. The cumulative effect of the Flemish migration is such that by one estimate almost one-in-three Scots have Flemish ancestry.

DNA from Flanders is, through inter-marriage, now well embedded in the Scottish population.

Many of today’s most prominent Scottish families can claim Flemish roots. The surname Fleming clearly signifies a Flemish origin but there are others such as the Sutherland, Murray, Innes and Lindsay families that were part of the early inflow of elite Flemish.

In fact, academics at St Andrews University have identified around 100 surnames which indicate Flemish ancestry.

Scone is derived from a Flemish word

The imprint of the Flemish has also been felt in many other ways, for example the absorption of Flemish words into the Scottish vocabulary. The Scots word ‘scone’, for instance, was derived from the Flemish ‘schoon’.

The Flemish are renowned for their medieval defensive fortifications. Evidence of this influence can still be seen today in mottes – that is earthen mounds that supported wooden bailey stockades – in various parts of Scotland.

Some Scottish place names reveal a Flemish influence. Several, for instance, carry names such as Flemington or Fleminghill. Other examples are Lamington and Roberton, which are named after Flemish settlers.

There has also been a discernible Flemish influence on Scottish architecture. This can be most readily seen in the orange pan tiles and crow steps that are features of a number of villages around the Forth estuary (these date from the era where Scotland would export wool and the Flemish would send back tiles, mainly to act as ballast).

Some Scottish churches have also benefited from a Flemish influence, notably the ceiling of King’s College Chapel in Aberdeen and the west front of the collegiate church of St Mary, Haddington.

Cultural and sporting influences have also been at play. Regarding the latter, there is a long-running debate surrounding a possible Flemish influence on golf and curling, pursuits that have long been considered to have their home in Scotland. Early Flemish paintings appear to portray games that have a resemblance to golf and curling before the time when these pursuits took hold in Scotland.

As one historian put it when commenting on the Flemish influence in Scotland: ‘They were a people who punched above their weight in the annals of Scottish history.’

- This feature was originally published in 2017.

TAGS