Just over 100 years ago, World War I came to an end.

In May 1916, the two greatest battle fleets the world had ever seen came together in a clash of arms off a little known peninsula of Denmark and fought a battle whose name has gone down in history.

Jutland was the biggest naval battle of the war and as it raged the world held its breath. For both sides had decided that Jutland was to be a decisive battle; as definitive a naval engagement as Trafalgar had been just over a century earlier.

It was long – 12 hours long – but Jutland was not that decisive an encounter and the principal question still remains: who won?

There is a compelling argument that, if Germany had prevailed at Jutland and broken the naval blockade being imposed by Britain’s superior navy then it would never have suffered the starvation that led it to embark on the U-boat campaign which brought America into the war and led to Germany’s ultimate defeat. Viewed through that prism, history should judge Jutland as a major British victory, yet the truth is not that simple.

The German and British fleets which entered the Great War in 1914 were the result of an arms race, which had been ongoing for over a decade before the outbreak and had its beginnings in the creation of Admiral Sir John Fisher’s famous dreadnought class battleships. What Fisher did for Britain, Tirpitz achieved in turn for the Kaiser.

By 1912, however, it became clear that Britain had won the dreadnought race and attention then focused on the development of the cruiser class. Here the future enemies had different philosophies. Fisher wanted heavier weapons in faster, smaller British ships and sacrificed armour to get it. The Germans’ more efficient engines, however, meant that their ships were as fast as their enemies, but also had heavier armour. And so the odds stacked up.

The destroyer, virtually invented by Fisher, gave the British an extra edge, but for their part the Germans excelled at building submarines – U-boats – and also defended their coast with a belt of underwater mines.

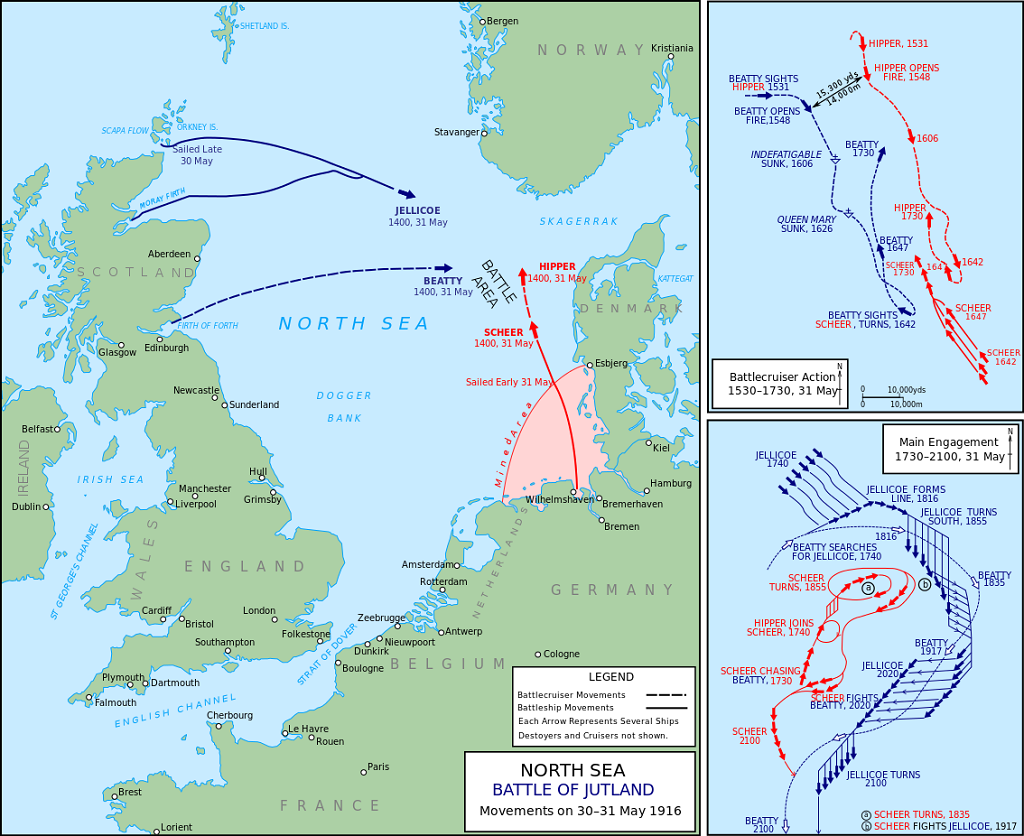

The Royal Navy fleet sailed from Scotland

The fact remained though that the Germans, with fewer ships, could never hope to defeat the entire British fleet in a pitched battle. And so their strategy evolved into attempting to lure a significant portion of the Royal Navy out of home waters to destroy it piecemeal.

Early in the war both fleets remained in harbour, the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow and the German High Seas Fleet at Wilhelmshaven. This inaction was followed by the tit-for-tat victories of Coronel, the Falklands and Helgoland. That December, the Kaiser’s navy sparked outrage by bombarding the British mainland at Hartlepool, Whitby and Scarborough, killing around a hundred civilians. These raids, with Zeppelin bombing and the emergence of unrestricted U-boat raiding on merchant ships, pushed the Royal Navy to the limits of provocation to retaliate.

On 23 May, the Germans planned a further attack, on Sunderland. Five days later, however, with poor weather, they decided instead to move to the Skaggerak, targeting British merchantmen using the 60-mile gap in northern waters.

But, with its superior intelligence, the Royal Navy discovered the German intentions and the British commander, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, put to sea with all but three battleships of the Grand Fleet.

The battle of Jutland began at around 3.45pm on the afternoon of 31 May, 1916, when five of Admiral Hipper’s German battlecruisers met six of those of the Royal Navy battlecruiser fleet, under Vice-Admiral Sir David Beatty.

A book, Jutland 1916: Twelve Hours to Win the War, by the distinguished historian and ex-Royal Navy officer Angus Konstam, tells that story with authority and (often gruesome) attention to detail. The essential plan

on both sides was to allow the cruisers to battle it out before sending in a fleet of dreadnoughts to mop up what was left and win the victory.

Shortly after 4pm, HMS Indefatigable took a telling hit to her stern, fired by the Von der Tann. The German ship then fired again and scored another hit, damaging the British ship’s steering. A third salvo struck Indefatigable’s A turret and a huge explosion was followed by a column of flame. Of her 1,019-man crew, only two survived. Within half an hour Beatty’s cruiser fleet lost another ship, HMS Queen Mary, blown to atoms with all but nine of her 1,275 crew.

It was the start of a 12-hour inferno in which Beatty displayed remarkable sangfroid (he is reputed to have said after the loss of the two cruisers that ‘there seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today’). But, if Hipper had won the first stage of the action by luring out the British vanguard, the Royal Navy now took the upper hand, in turn drawing in much of the German force.

For the next four hours, as night fell, more than 250 ships fought an intense battle. Throughout the night, Jellicoe attempted to prolong the engagement, knowing that if he could bring the German fleet to battle again, he stood a chance of victory. But Scheer managed to slip away and the advantage was lost.

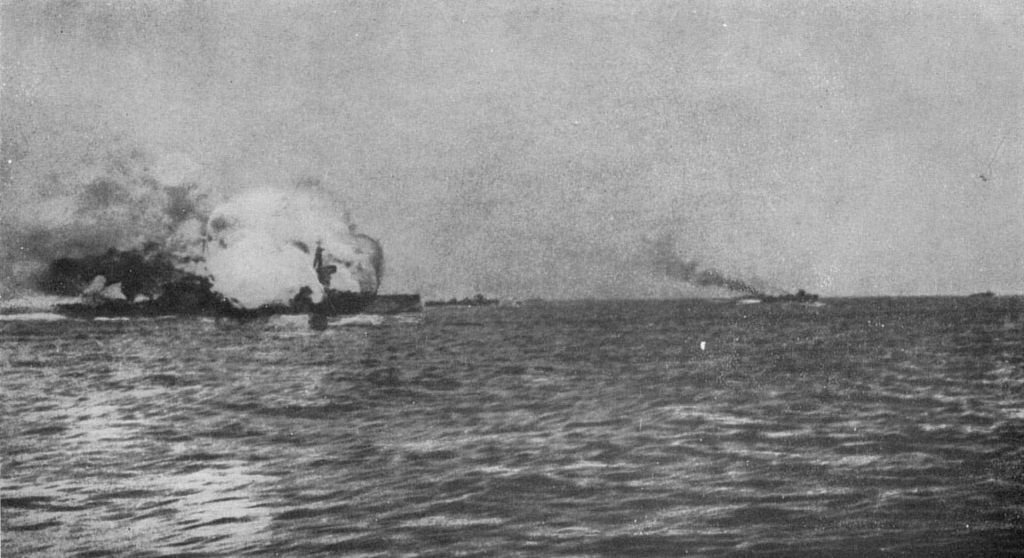

The battle was marked by moments of supreme horror: from incinerating fireballs and deliberate flooding to save ships, which resulted in mass drownings, to the living hell of exploding magazines.

The explosion, marking the destruction of HMS Invincible

In all, the Royal Navy lost 14 ships and the Germans 11. There were also twice as many British dead as German, some 6,800 to just over 3,000. Both Beatty and Jellicoe have been vilified, and both have their supporters and detractors.

Konstam, however, shrewdly points out that, had it not been for the 3,000 men lost on three British cruisers, then casualties would have been roughly equal. He attributes this to the fatal lack of armour on the British ships, laying the blame for that deficiency at Fisher’s feet. He also points out that, while on the Western Front in the ground

war few generals or colonels were killed, at Jutland no less than three admirals and 18 ships’ captains perished. (He does forget, however, that on the first day of the Somme no less than 50 colonels died).

But while the British may have suffered more than the Germans, their fleet recovered at an astonishing rate and on the evening of 2 June, a total of 23 British dreadnoughts, a battleship and three battlecruisers, were available for duty, while in the German High Seas Fleet only nine dreadnoughts were battle-ready. At the end of the day, Britannia still ruled the waves.

Despite this fact, the immediate aftermath was ironic and telling. The Germans won an instant propaganda war so effectively that, as British wounded sailors came ashore in Scotland a full day after the Germans had berthed, they were actually jeered by workers who had read about a terrible British defeat.

But in the end it was the Germans who would lose. After Jutland they would never break the blockade and as a result their people would starve. Driven to further use of U-boats, they unwittingly compelled the USA to enter a war they could never then win.

That is the real consequence of Jutland – a definitive British victory.

However, it was not the great victory that the British public had wanted or expected and the Royal Navy never really recovered. In so many ways, Jutland was yet another tragedy in a war which gave new and terrible meaning to the word.

This feature was first published in 2016.

TAGS