A happy coincidence of tourism and therapy made Scotland’s hydropathic hotels a Victorian sensation, but their popularity just couldn’t last.

The stereotypical view of 19th-century Scottish industry is not the most romantic of pictures: coal-mining across the Central Belt to fuel the Empire; shipbuilding on Clydeside to defend the Empire and to extend its commercial reach; the grandiose offices of the tobacco, tea and sugar lords, the beneficiaries of the Empire’s power and market.

But it is often forgotten that this manufacturing and mercantile economy was not the whole picture. Victorian Scotland also had a burgeoning service sector, and the most remarkable legacy of its status as a tourist destination is the almost nostalgic image of the hydropathic hotel, the country’s answer to the great seaside resorts and spa towns of England. Some of these places have been refurbished as contemporary luxury hotels; others have become university buildings; a few lie derelict.

The hydrotherapy movement proper was founded by Vincent Priessnitz, a Silesian peasant who lived between 1799 and 1851.

Priessnitz purportedly became curious about the healing power of water after seeing a roe deer limping to a pond to bathe its wounded limb; he later experimented on himself, and on his neighbours. By 1822 he had converted part of his father’s farm to a sanatorium, and four years later his fame was such that he was invited to treat the brother of the Holy Roman Emperor. Roy Porter, a historian of medicine, states that Priessnitz treated 22 princes, 149 counts and countesses, a duke and a duchess, and worked with 120 doctors.

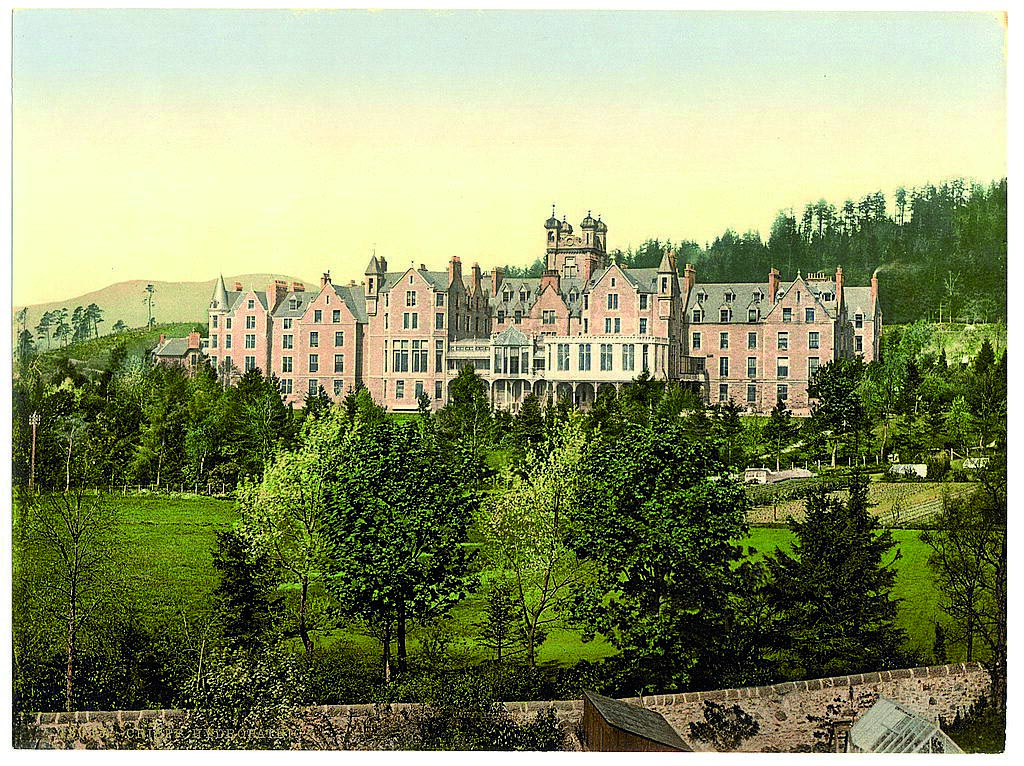

The plunge pool at the

Atholl Palace

Captain Richard Claridge, a British asphalt contractor, popularised the idea to an Englishspeaking audience with Hydropathy, or The Cold Water Cure, as practised by Vincent Priessnitz in 1842. A throwaway remark of Priessnitz’s was to have an immense impact on Scotland. Despite plying his trade in all manner of landscape, he supposedly once remarked ‘Man muss Gebirge haben’ – ‘One must have mountains.’

There were water cures in Britain before Priessnitz came along; a belief in the beneficial effects of sea-bathing was what carried Robert Burns to an early grave. And Bath had already emerged as a spa town by the end of the 18th century – the infant Walter Scott was treated there for his polio, while Jane Austen’s unfinished Sanditon satirised the hypochondriacs of the town.

In Scotland, the pump room was built in Strathpeffer in 1819 to exploit the sulphurous springs; and a traditional spring at Innerleithen became an unlikely health destination after appearing in Scott’s St Ronan’s Well, with entrepreneurs claiming it cured everything from rheumatism to infertility. But these spas relied more on ingesting the waters than bathing in them.

Although The Lancet described the work of Captain Claridge as that of a quack and a charlatan, hydropathic institutions sprang up immediately. More than 50 were created in Britain in the Victorian era, with a disproportionate number – 20-plus – in Scotland. The earliest, the Glenburn Hydro, was founded in Rothesay in 1843, while the last, Callander Hydro, was built in 1882. The construction of both Morningside Hydro and Oban Hydro started later still, but neither project was completed, signalling the beginning of the end of the hydro boom.

Crieff Hydro

Priessnitz’s off-the-cuff comment about mountain waters clearly chimed with Scottish hydropathic interests, and the prevalence of mineral waters today which trade on the association (such as Highland Spring) is a remnant of this former significance.

James Bradley, Marguerite Dupree and Alastair Durie of the Wellcome Unit for the History of Medicine at Glasgow University have compiled some astonishing statistics about the rise of the Scottish hydropathics. Between 1875 and 1884, more than half of the total capital mobilised in the service sector was due to the 14 hydropathics that were limited liability companies (a figure that excludes the ‘success stories’ of Peebles and Crieff Hydros).

Although the earliest hydros, at Bridge of Allan, Dunoon, Gilmourhill and Angusfield, were moderately sized, having fewer than 50 rooms, later buildings, such as Moffat, had 300 rooms. The success of the hydro hotels was in their unique combination of tourism and medicine.

It is no coincidence that one of the first tours by Thomas Cook, where 350 people went from Leicester to Scotland, was in 1846; or that Queen Victoria’s Highland holiday home of Balmoral was completed in 1856.

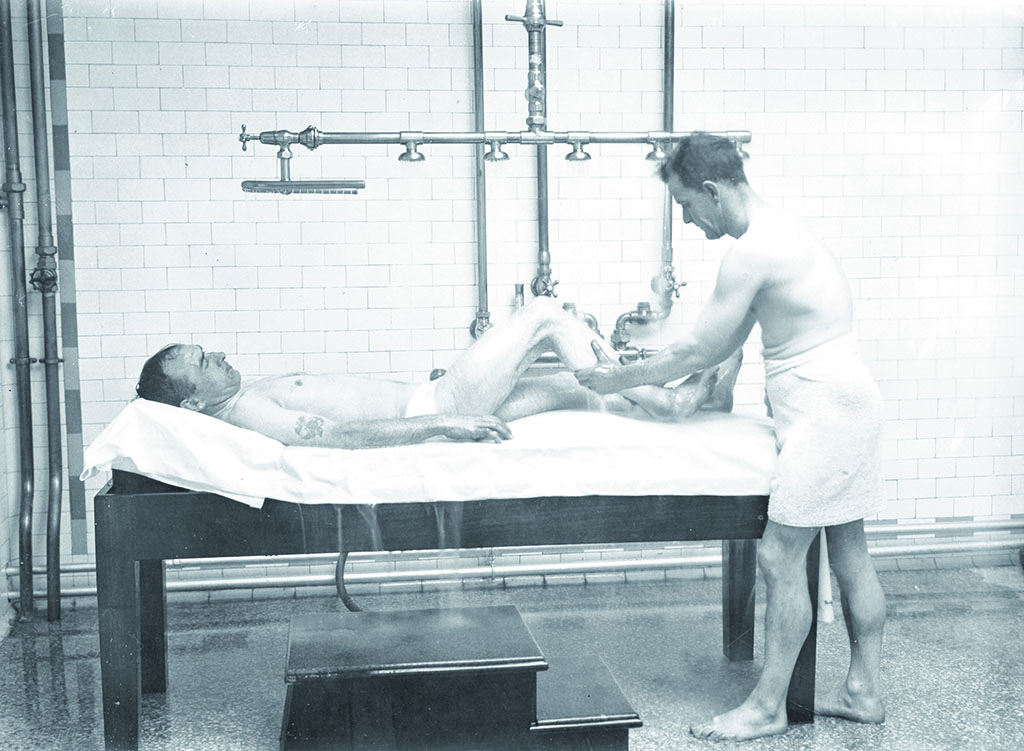

Massage therapy

The hydros had high-profile advocates. Mark Twain enjoyed his trip to a European hydro so much that ‘if I hadn’t had a disease I’d have borrowed one just to have a pretext for going on’. The novelist Lord Lytton enthused about his experiences in Confessions of a Water Patient, describing the ‘exquisite pleasure in the sense of being’ and ‘religious joy’ the rest-cure created.

The medicinal regime of the hydropathics was diverse: ‘compressing’ with hot and cold wet towels to encourage sweating and cooling; steam baths and ‘hot air’ baths; full immersion baths (both hot and cold); various poultices, mustard plasters and spongings; and, of course, water-drinking. Most also included dietary strictures, exercise and walking in the open air.

As they became more successful, Scotland’s hydros laid on more conventional tourist attractions: golf courses, resident pianists, billiard rooms and evening concerts. The clientele was affl uent, and the Scotsman of 6 September 1900 devoted a large section to the capture of a jewel thief at Moffat Hydro (the villain was ‘indifferent to his situation and smoked a cigarette’).

Ironically, all the hydros began life as ‘dry’ (ie alcohol-free) institutions (in the case of Crieff, up to the 1970s). The Peebles local paper called the hydro ‘a great hotel, minus the liquor and late hours, plus the baths’. In James Rae’s Jeems at the Hidrapathic, two Glaswegians en route to the Rothesay Hydro stop at an inn and demand of the landlady: ‘As we’re gaun awa’ tae a place where we’ll get naething but watter, ye’ll better fill oor pistols and this waulking stick with the “Auld Kirk” an’ mak’ us ready.’ Two factors led to the decline of the hydropathics.

A bizarre electro-therapeutic device at Peebles Hydro

Firstly, analgesics and anti biotics reduced the reliance on alternative remedies (aspirin was first commercially produced in 1899, penicillin in 1928). Secondly, the hydros were requisitioned as military hospitals in the Great War, most famously Craiglockhart, where the poets Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon were treated for shell-shock. Some continued after the war, but their status was much declined.

The writer John Buchan gave perhaps the best description of the hydro in Huntingtower, his first novel featuring the 55-year-old grocer Dickson McCunn. It was a description full of satire and yet tinged with nostalgia: ‘He knew that for his wife earthly paradise was a hydropathic, where she put on her afternoon dress and every jewel she possessed when she rose in the morning, ate large meals of which the novelty atoned for the nastiness, and collected an immense casual acquaintance, with whom she discussed ailments, ministers, sudden deaths and the intricate genealogies of her class.

‘For his part he rancorously hated hydropathics, having once spent a black week under the roof of one in his wife’s company. He detested the food, the Turkish baths (he had a passionate aversion to baring his body before strangers), the inability to find anything to do and the compulsion to endless small talk.’

This feature was originally published in 2012.

TAGS