Caledonia’s calling for songwriter Dougie MacLean

Perthshire’s Dougie MacLean is known the world over for his anthem born out of homesickness, but Scotland’s finest singer-songwriter has many more strings to his bow…

It’s funny how life can come full circle. I grew up here in Butterstone, by Dunkeld and went to the old village school – I went to it, and my father and his two brothers went to it in the 1930s.

I grew up in a wee house just up the road, so I haven’t really moved more than a couple of miles from this area. When the school closed in the 1970s it lay empty for a long, long time, then I was able to buy it. We also bought the old teacher’s house, which my mum used to clean. We live in it now – it’s really bizarre!

We joined the house and school together and now have the school as a recording studio. Outside is the old playing field and the oak wood where I used to play as a kid. There is a great sense of continuity, which I love.

My family was originally from Argyllshire. The MacLean side of the family all come from the west coast of Mull and my mum’s folk are all from around Taynuilt. But being itinerant shepherds and workers on the land, they moved about and came down to Perthshire in the 1920s.

My grandfather was a shepherd on the hills above Butterstone and my father was gardener on a big estate. It was an idyllic upbringing. My cousins and I spent most of our time out in the woods – that was our playground. It was also wonderful having my grandfather and father about. They would take you out and show you all these things, so you got to know the landscape really well. It becomes part of you.

As we got older, we would be out working in the fields. It was all tenant farmers around us, so when the tatties were being lifted, as a ten-year-old you were out in the fields helping.

All the kids from all the different families would be working in the fields. We helped each other but, of course, we needed the money too. You were all poor, so there was nobody better than anyone else. Mums and dads were doing their best to put food on the table for their kids.

So we’d be picking tatties alongside the travelling people who were living in the camps up by the woods. It’s that upbringing that has kept me grounded over the years.

Music was always part of our life. My father passed away a few years ago aged 83, but Mum’s still alive. She’s 80, and still plays the melodeon – I’ve got her original melodeon in the studio.

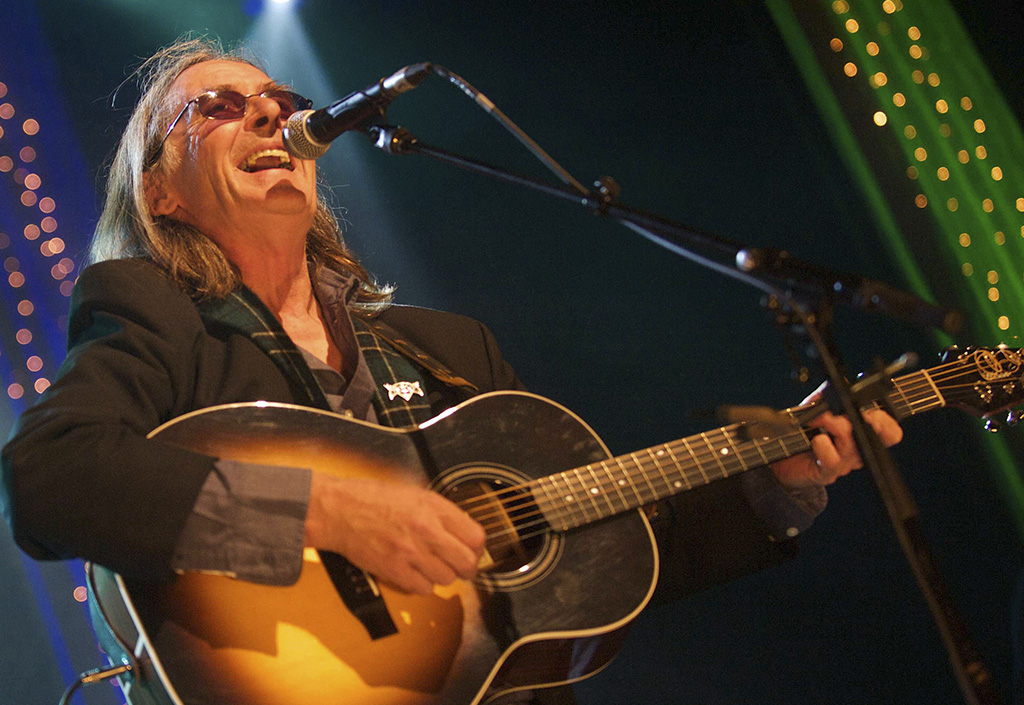

Dougie MacLean performing (Photo: Rob McDougall)

My dad played a wee bit of fiddle. They loved music and so it wasn’t unknown, if there was a party in the house, for the table to be pushed back and Mum to get the melodeon out and my uncles would come and play their melodeons.

So I started on the melodeon. I had a good ear – both my mother and father had good musical ears and could play by ear – so I learned to play harmonica quite young. I was about five years old and I could play ‘Morag of Dunvegan’ on the harmonica.

I did my first performance in the little village hall up the road. The village halls were a big deal in those days. The Scottish country dance bands would come at the weekends and my mum and dad would drag me and my sister round all these village halls within two or three miles of home. My big dream when I was a kid was to be a drummer in a Scottish dance band! But singing was my thing. I really enjoyed it. My sister’s musical too – she never took it anywhere but we used to sing together a lot.

It was that rural, village hall tradition that got me interested in folk music. I have memories of my grandfather singing beautiful old Gaelic songs and the tears running down his face. Seanair – which is Gaelic for ‘grandfather’ – would sing these songs and as wee kids we’d be fascinated by him. You pick up on all that by osmosis. Music becomes a different part of your life, not just something you listen to on records.

And it wasn’t just folk music: I was a big Beatles fan and a big Deep Purple fan, but I was lucky I had a connection to that – it was in the house and it wasn’t a mystery to me. So it was quite natural when I started playing.

I’m totally self-taught. We always used to make up songs – that was part of growing up here. I remember one of the things that changed things for me was my father wanted a mandolin. So my sister and I went to Perth and bought him one, and on the way back on the bus I remember sitting playing the mandolin and I thought, ‘Gosh, I can play wee tunes on this.’ So I started playing the mandolin.

When I was at high school in Perth – I was about 15 or 16, so it would be the late 1960s – there was a big folk revival, so it was quite hip to be into folk music.

There were a few of us at high school who used to get together at lunchtime and play folk tunes. A guy called Ewan Sutherland and I got together as a wee duo and we’d play the Angus Hotel in Blairgowrie for the skiers – I think we got paid £1 a night. I would play mandolin and he would sing Corries songs. We loved it. Ewan and I then developed our band and I got a few more of my high school pals together to form Puddock’s Well. That was when I learned to play fiddle. When I started, I quickly realised I knew all these tunes because I’d been listening to them in the village halls since I was a wee boy, so I didn’t need to learn any.

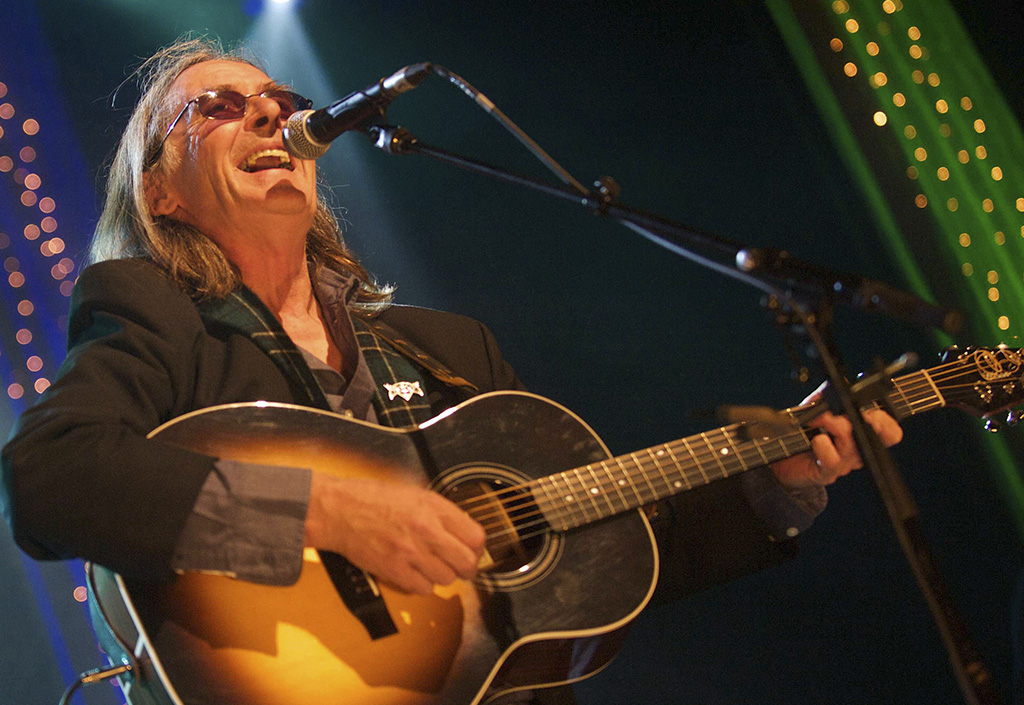

Dougie MacLean relaxing and ready to play (Photo: Angus Blackburn)

Around that time I joined the Tannahill Weavers, playing fiddle. I was working in Aberdeen as a gardener and the Weavers had just lost their fiddle player. One day their van pulled up and Roy jumped out and he says, ‘Dougie, do you want to join a band? We’re off to Germany tomorrow!’ So I went back to my friends and said, ‘I’ve just been asked to join the Tannahills, what do you think I should do?’ They said, ‘Do it or you’ll regret it for the rest of your life.’

So that night I gave up my job and my flat and the next day I was driving this old Transit van onto the ferry to do these wee gigs in Germany. Had I not made that decision then, I probably would never have got into music full time. It’s funny how you can trace things back to one decision and having good friends around who knew how much I loved music.

It was a popular time for folk music in Europe, so we toured all over the continent. I’d always sung, but I didn’t sing in the band. I would write wee songs, but they wouldn’t let me sing them.

There came a point when I decided songwriting and singing was what I wanted to do and left the band. It’s quite a jump to go on your own, but I was lucky. A dear late friend of mine, Alan Roberts, who was living in Germany, called me up and said, ‘Why don’t you come over and we’ll go out as a duo’ – he played guitar and I played fiddle. I needed to make a living so I went over and we started touring.

I started introducing my own songs into our performance, which allowed me to gain confidence and realise I was creating something people were enjoying. That was about the time I wrote Caledonia. I remember I had some time off and I went away busking with some French guys and wrote Caledonia on a beach. The first time I ever sang it was at a concert in West Berlin. Alan and I worked out a lovely two guitar part and people loved it. So I thought, we’ll keep that one in the set!

The catalyst for the song was homesickness. I love this place and I often wonder had I not grown up in beautiful Perthshire, would I have written the song? I was as much homesick for Perthshire as I was for Scotland. I used to love coming home. One thing about doing a lot of travelling is that I realised the place you feel most comfortable is where you grew up. You can look at the sky and tell what kind of day it’s going to be. I love the intimacy you have with the landscape, the seasons and the people.

Caledonia has become so much part of the Scottish psyche, but it has done it off its own back. It has come to mean more about that sense of belonging than about Scotland. People sing it at weddings, they sing it at funerals – it becomes a kind of tool that people use in their everyday life. Music is much more than just a commodity. When it’s done right it’s a tool in life’s toolbox to keep you from getting depressed or for celebrating in your own home. And Caledonia has done that.

When I wrote it I was a young boy and genuinely homesick. I didn’t have the baggage of the world, so the words are simple, the concept’s simple. Maybe if I’d been too flowery with the lyrics it wouldn’t have connected with people. It’s a magical thing when you put a bunch of words with a melody. When it works, it’s really powerful. But you have to be emotionally open to it all. It’s not cool to be sentimental. But I grew up in a sentimental family and it was a lovely thing and not something we were embarrassed about or felt we had to hide. So, yeah, I’m not cool!

Living here, in a bit of isolation is good. It keeps you pure and not affected by watching what other people are doing, so you end up being true to yourself. And when it’s true to you, it’s authentic, it’s real and it has got something to say. So I owe my career to my environs.

Dougie MacLean braving the Perthshire rain (Photo: Angus Blackburn)

When Jenny and I decided to move back to Perthshire, everybody said you couldn’t have a successful music career from Scotland, you had to go to London or New York. I was working with an English company but we decided to come back here and set up our own independent record company in Perthshire. We were one of the first to do that.

I remember when we made the first record up here. It was the days of vinyl and there were no cutting rooms in Scotland, so I had to get on one of the very first Stagecoach overnight buses to Soho – buses that I used to go to school in. The driver would stop the bus halfway down to London with the thermos flask and the wee rolls!

So we persevered and over the years it has been a brilliant thing. I’ve forged my own way and I encourage people to do that too, to find their own personality. Because your music is you, otherwise you don’t have anything to say that’s unique when you stand up on stage.

And doing my own thing led to me setting up Perthshire Amber Festival {the 2019 event ran from 1-3 November]. We thought it would be a great idea to try to encourage a lot of my fans to come and visit the place the songs were written about, see what inspired the music. So the festival started off as a weekend and it has grown to ten days.

We didn’t want it to just be concerts, but also walks and talks, get people out exploring Perthshire, because it’s beautiful. We try to put on shows in unique venues – people can go to theatres in their own towns but they can’t go to the medieval cathedral in Dunkeld or the great hall in Blair Castle and hear a concert. Last year we did an economic impact study and about 40% of our visitors come from outside the UK, with the festival bringing £1.2m into the Perthshire economy. It’s great to be able to give something back.

My big thing at the moment is Butterstone TV, which we set up and use to broadcast from the festival. My son and my daughter and I, we’re all quite technically minded. It runs in the family. My Uncle Archie, who lived up the hill at the back of us taught himself to fix black-and-white televisions. . I’m sure I inherited that skill.

I remember quite early on, I came back from America and I said to Jenny, ‘There’s something we should look at, it’s called the world wide web’! So we were among the first people to take that technology on board and create our own website. When Jenny and I owned a little music pub in Dunkeld, we used to do wee audio broadcasts from there using technology to get our music out there.

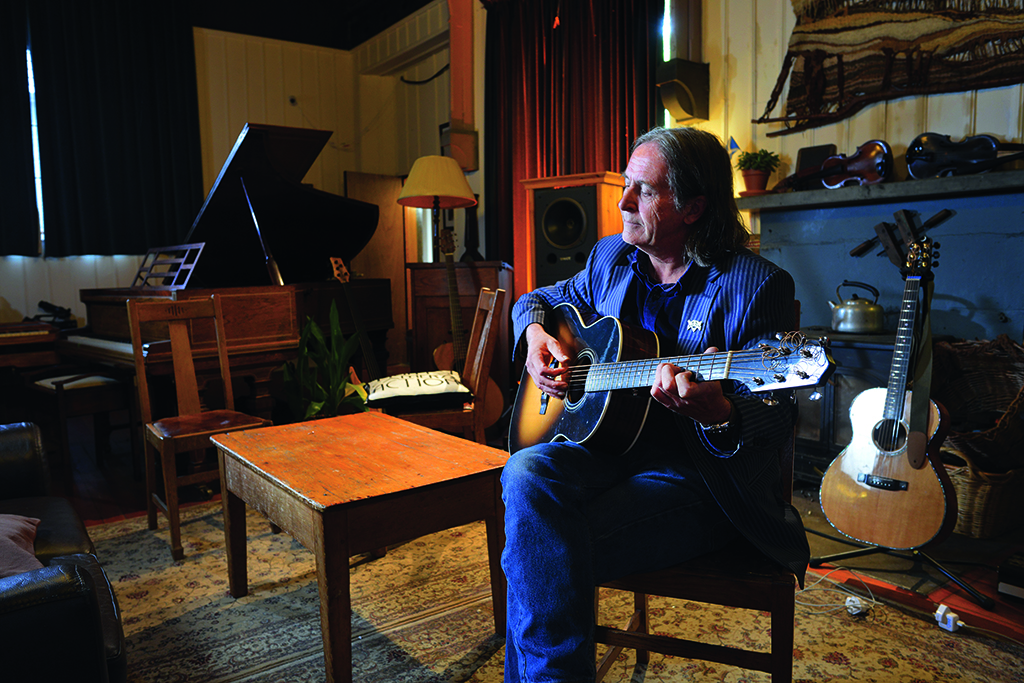

Dougie MacLean, with writer of Caledonia (Photo: Angus Blackburn)

Butterstone TV is now in its third year and we’ve broadcast our sold-out shows at the festivals and we also broadcast from my studio. We shoot with four cameras and broadcast live. So, for example, I might be doing a concert up in Aberfeldy town hall, but a lot of people in Florida, New Zealand and Australia will all be watching it live at home.

The last Christmas broadcast was filmed in my studio. We laugh, because my father learned to write with a piece of chalk in that school and now we’re out there broadcasting to the whole planet. It’s mind-boggling.

With Butterstone TV I’ve tried to invent a model. I spent a lot of time touring in America but I don’t necessarily want to be doing that now. However, I’m still really active on the writing side, so it’s a great way of being able to keep in touch with people.

One of the lovely things about working away myself for years and years is when you get recognition from outside. When I received my OBE it was a big day for my mum. I phoned her up and I said, ‘Go and buy a hat, you’re going to meet the Queen’. She thought I was kidding! It was a big deal for her – she worked so hard, my mum. I don’t make a big deal of it, but it was a nice complement to get.

I’ve got a lot of awards over the years – including two prestigious Tartan Clef Awards, a place in the Scottish Music Hall of Fame and a Lifetime Achievement Award from BBC Radio 2 Folk Awards – and it’s always nice to get recognised by your peers for what you do.

But the important thing is that I still have a passion for music. I’ve actually started writing an album of children’s songs – songs I wrote for my own kids and grandkids – and I’ve just finished writing a musical script. I’ve never done anything like this before but it has been a brilliant experience.

(This feature was originally published in 2015)

TAGS