Glasgow is a huge influence on Chris Brookmyre

The Bloody Scotland crime writing festival is taking place in Stirling this weekend.

One of the guests this year is the acclaimed Christopher Brookmyre.

He tells Scottish Field about his life and influences.

As a writer, I’ve always thought Barrhead was a great place to grow up because you got a sense of all of society – it had both its poorer and more affluent areas – which meant you didn’t get a skewed perspective of what life outside it was like. But Glasgow has probably been the bigger influence on me personally and on my work.

I went to university in Glasgow to study English – your classic stay-at-home-to-go-to-uni Glaswegian – but it was as I got a bit older, with the freedom to go about the city, I got a better sense of the aesthetics of it and I felt proud of what a beautiful city it was.

Then, after graduating and getting my first job in journalism, I went to work in London and became very aware of what a misperception people had of Glasgow. They imagined it as some massive slum, but I was trying to say no, this was the second city of Empire, this is a city of opulent architecture, of great note in terms of its artistic heritage. I think artistically I was waging a campaign to celebrate a lot of Glasgow’s positive cultural aspects in my work.

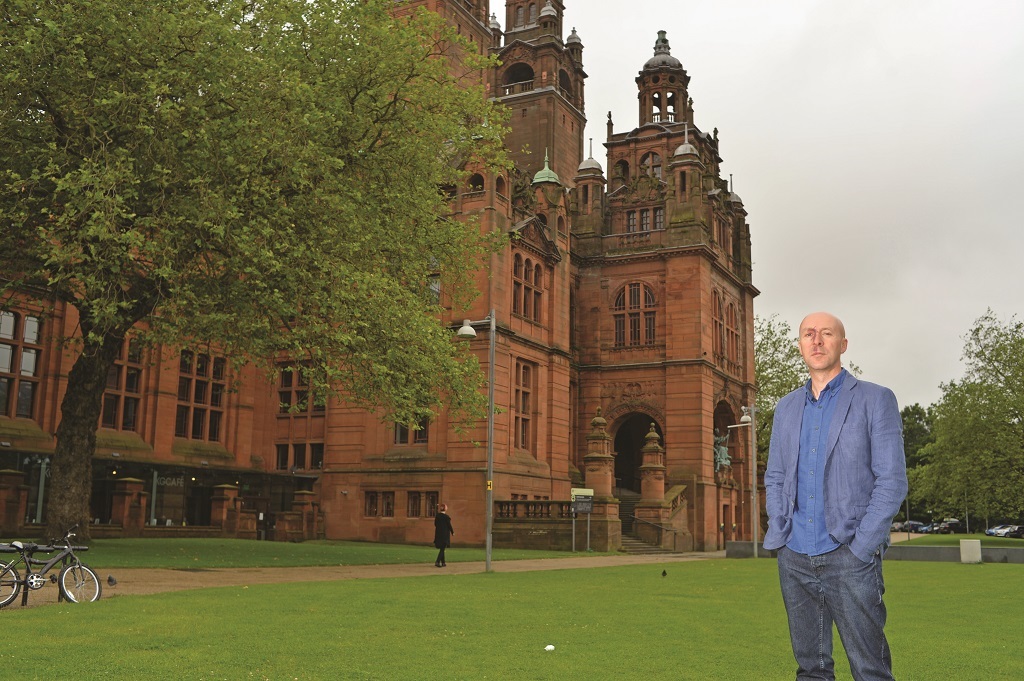

Chris Brookmyre at Kelvingrove

Back in the early nineties when Steve Martin was in his movie LA Story, there was an American film maker called John Singleton who was very critical of it because he said it just wasn’t real. Again, it was the fairy story of LA that completely ignored the reality for a lot of people in LA, particularly the black community, and I understood his frustration. I thought we had the opposite – every time Glasgow was depicted in popular culture it was about violence, it was about drugs, it was about poverty, and I would never argue that we shouldn’t depict that, but I always felt that we only get that version and there’s more to Glasgow than that.

So I always wanted to write crime stories that showed Glasgow in a slightly more, not glamorous light, but that showed both sides. Yes, here is that side but here’s the other – this is a forward-looking city and there’s more to it than the same story being told over and over again. I’ve always felt quite proud of my city and wanted to show that it’s a very complex and multifaceted place.

Take my book, The Sacred Art of Stealing, which features a bank robbery. The bank I based it on is now Saints and Sinners clothing shop. This is probably the book I think of most when thinking about Glasgow and how characters are shaped by Glasgow.

It’s about the dark side but the book I think of when wanting to showcase Glasgow as being about more than that. It’s quite a – within reason – glamorous book. It’s about a magician who uses techniques of stage management to commit robberies. So it’s kind of about art and culture, and all the different sides of Glasgow represented in that book.

The language in Glasgow has also had a big influence on me. I remember at school the teachers being disapproving of the use of slang and I almost felt like they were trying to beat your accent out of you.

I remember in William McIlvanney’s book, Docherty, he talks about his character getting belted at school for using Scots words, so I really prized that. I thought Glasgow was very rich for its language, whether it’s the slang or the dialect, for the way it uses language and I always felt that should be celebrated rather than discouraged. I also wanted to bring the language and the slang into crime fiction because I think it really belongs there.

And I don’t think you can’t divorce the language of Glasgow with the attitude in Glasgow. Some people find it quite confrontational but I think the directness isn’t as confrontational as people think. I think the directness is just about getting to the point, whether that’s maleficent or malevolent, and it can be both.

Chris Brookmyre looks over the River Clyde

As a student, and later as a writer, I spent a lot of time in Mitchell Library. I’d come down here because it was a different atmosphere. I found it quite inspirational as a place – I think it has a real sense of Glasgow’s history about it and I always felt quite privileged as a student to have a library ticket to go and use it – but it’s a ticket anybody and everybody can have.

Actually, in my book Flesh Wounds (the third book in the Jasmine Sharp trilogy), the cop discovers a Mitchell Library ticket in the possession of this dead drug dealer and realises drug dealers tend not to go to the library, so senses there must be a very good reason why this guy has a ticket for the Mitchell Library!

When I moved down to London and would come back here at the weekend, I’d drive passed it on the motorway or at night when it was all lit up, and it was always one of the places that made me homesick. I’d think of it when I wasn’t there, and when I was up for the weekend and saw the Mitchell I’d think, I wish I lived here.

As a student you’ve got certain freedoms but you never have any money, and when I was living in London and had a regular income, I kind a missed Glasgow and wished I could be there with a job and money in my pocket. It was always the Mitchell I tended to think of – in my head it was a kind of icon for everything I love about Glasgow. It has turned up in a couple of my books because it has a special place in my heart and my imagination.

I think growing up, my parents’ perspective on things was infused into me. They’re both quite irreverent in their sense of humour and they’re both always very politically engaged. When you were sitting round the table you were encouraged to contribute, but equally, if your contribution was mince, you were going to get ridiculed for it, so it was a good lesson in making sure if you had something to say, it stands up.

One of the things I think I benefited from is my dad has always been a very calm individual, and what I took from that is that there are very few things in life worth getting really upset about. You can always see the funny side of things so I think that helped me to be quite analytical and see both sides of a situation, which is crucial for a writer because it’s easy enough to create the kind of cartoon villains, but the villains get a lot more interesting when you try to understand their motivation.

Writer Chris Brookmyre

One thing that amuses me, especially with the early books where at times they are quite outrageous, people ask are your parents OK with these, and I say, where do you think my sense of humour came from? I grew up in a house where there was always laughter, it was prized if you could say something funny, and yet perceptive. So humour is hugely important in my writing.

I think I wrote three novels before I was published when I was trying to write something more serious, cos I thought that’s what publishers wanted. But I wasn’t really being true to myself. It was when I realised my natural ideom for writing was quite humorous, that’s when I realised what I should be doing, because if felt natural and it flowed a lot better.

Humour provided a soundtrack to my childhood. Billy Connolly, Monty Python, Bill Hicks – these were the types of voices in my head when I was writing. Billy Connolly was all about characters and situations and language that you recognise, and Bill Hicks was quite philosophical, making jokes about everything from sex, global politics. I always like something that is funny yet true. But at the same time I absolutely adored Monty Python as a kid, stuff that’s funny because it’s stupid and strange. I find really absurd things very funny. I love Burniston because that’s got a combination of the absurd and the recognisable Glaswegian traits.

When I finally found my voice, to use that cliche, my idea of an adult book was one that had good guys, bad guys, perplexing and highly implausible plots and, if possible, a top secret underground military base. I always enjoyed thrillers and that’s what I thought I was writing until people started applying the term crime fiction. To me at that time crime fiction was always about sleuthing.

I just thought I was writing thrillers, adventure stories and comedy, so I didn’t see my work as part of that genre, and I certainly don’t see it as it as noir.

I tend to think of my books as colourful and escapist, and generally quite happy. I think for the most part the good guys win and they’re meant to give the reader a sense of well being by the end, they’re not grim existential pieces.

- This interview originally appeared in Scottish Field’s October 2015 edition.

TAGS