Sir Alex Ferguson – a winner born and bred in Govan

Scotland’s most successful football manager Sir Alex Ferguson explains how his personality was forged by growing up in Glasgow.

In 2011, Sir Alex Ferguson spoke to Scottish Field editor Richard Bath in an interview for the Glasgow Marketing Board, about being made in Glasgow.

The former Aberdeen and Manchester United boss won every domestic trophy on both sides of the borders, as well as European trophies with both clubs.

Govan was a shipbuilding town of course. With the shipyards and the dry dock it was a real hub.

The population of Govan before the war was 147,000 people, and now it’s 20,000. That tells you the devastation there was in the shipyards and what that created because it’s not just the shipyards themselves, it’s all the automotive industry and the light engineering, right up Helen Street. It was a massive area of engineering that was lost as soon as the shipyards went.

I grew up opposite Harland & Wolff, so I had to live through the noise of the night-shift workers banging around. The corkers’ hammers were going all night, but I got used to that. You’d sleep through that.

You didn’t have a lot but I never call it poverty because I don’t think it was poverty. You always had your meals, you never missed school, you were always clean and tidy. We didn’t have a bathroom but we did have a big zinc bath and you’d have your bath once a week and be scrubbed clean. Everybody was the same.

I know there were poor families; there were a lot of big families. I remember the Law family: Mrs Law had 18 kids and they were living in a tenement like all of us. I remember one of the sons, Joe, coming back from fighting in Korea and they were all there. It was like the coronation! I kept saying, ‘what’s all that bunting for?’ because the whole street was covered. There were uncles, aunties, cousins, brothers everywhere – it was a fantastic homecoming.

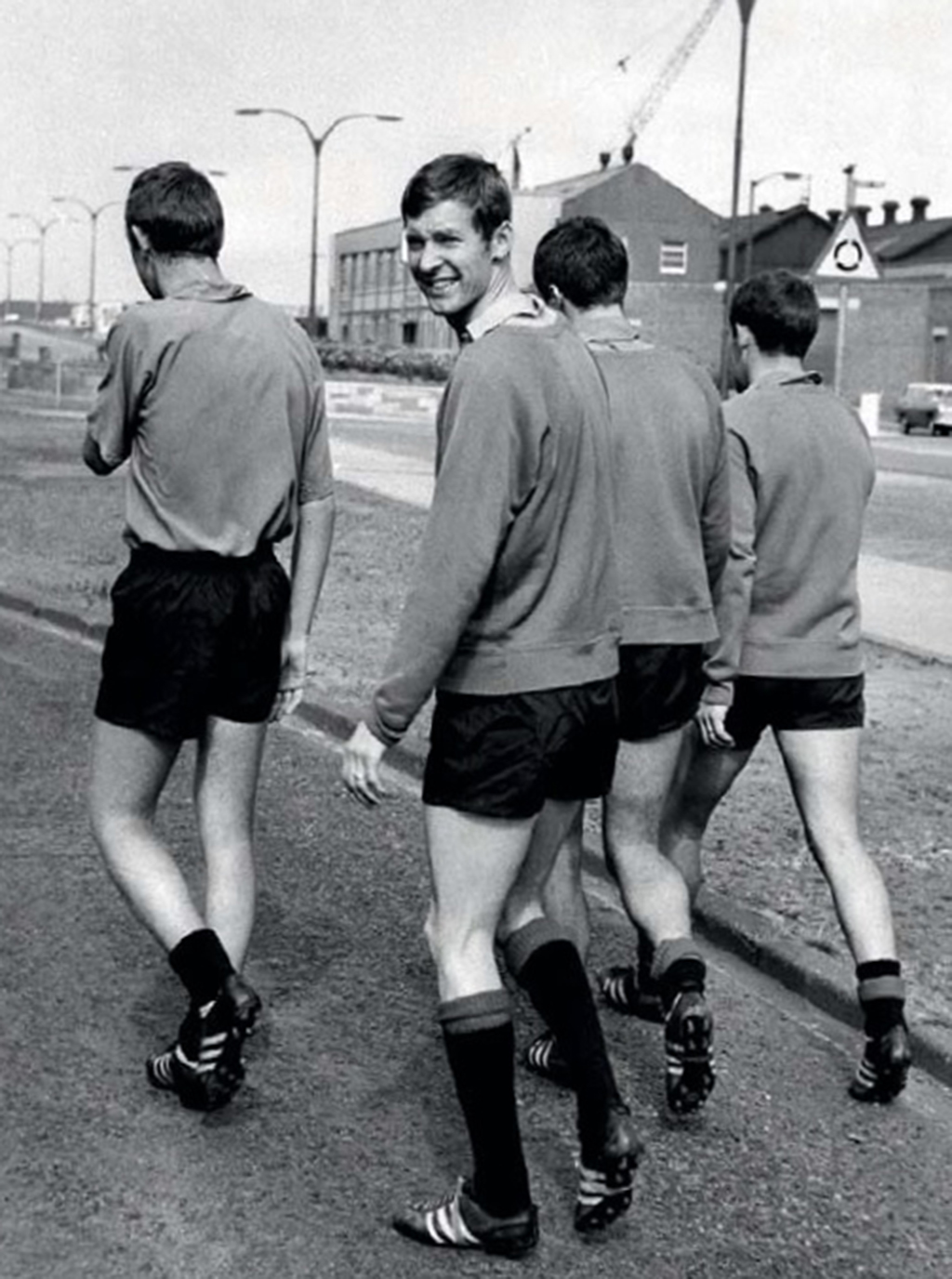

A young Alex Ferguson

It was a great upbringing. All we ever did was play football and fight. That’s what you did in these areas. There was a real sense of community because we all lived so close together. You hear it said that you never locked your door, but it’s true. You’d come in one day and you’d find a note: ‘Lizzie, I’ve taken a cup of sugar’ or ‘Lizzie, I’ve borrowed some tea’, that type of thing. People shared with each other. There was a common cause to help each other, far more than you get today. You knew all your neighbours and probably worked with half of them. It created healthy friendships you carry throughout your life.

The whole of my Hampden Old Boys Club team come down to Manchester every year and every one’s been married over 40 years. That’s unbelievable. All 12 of the team come down every year with their wives and we spend a great weekend. We’ve always kept pals since we played together at nine and ten years of age. We’ll always remain pals.

The passion and intensity of Glasgow is unbelievable. I was at the Rangers versus Celtic match recently. I looked around and saw all these guys with the veins on their necks sticking out. That’s because for most Glaswegians the only thing that matters is football. As kids all we ever did was play football; every day, all the time. We grew up in tenements so we spent all our time outside. Our mothers would say ‘get out there and get some fresh air’ so you were always out the back fi ghting with the gangs up the road and playing football. That was your life.

And we’d be out jumping dykes. Some areas of Govan had great jumps, where you could jump from one dyke to another. The dangerous ones had names: the king, the queen, the suicide, the diamond, the spiky. You’d go to different areas of Govan to challenge each other into jumping dykes because it was very dangerous. But you do that when you’re a kid because you’ve got no fear. We used to go for pigeons, go on church roofs, on bridges and that, you never worried about falling. Nowadays I’m in a 20-storey hotel and I look down and go “oh, for pity’s sake!” but when you’re young nothing worries you.’

Growing up, I had the self-confidence to stand up and lead. That was just within me. I was a wee bit bossy when I was younger; you get some guys who stand out in that way. It’s just a characteristic thing about me: being decisive and go-ahead, at times even aggressive.

I’ve always been like that, never changed. That aggression is a Glaswegian thing, especially with guys of my generation. I meet guys throughout the world and hear the Scottish accent and I say ‘where are you from?’ and they’re ‘I’m frae Glasgow’. It’s amazing how many are out there. They go out there because they have that determination to do well.

I went to do a documentary of myself which never got finished because the lad who was doing it got cancer. But I went down to Glasgow and down to the shipyards and I phoned up Joe Donnelly, the personnel manager my dad was pally with, and asked if I could go into the shipyard to do some fi lming and he said ‘yeah, come on in’. So they organised lunch in the boardroom and we went around the shipyard and it was all ‘hiya Alex’. And we went onto the deck of this ship and it was absolutely freezing. Honest to god, the wind was howling down the Clyde.

It was just a young interviewer and he said ‘what do you think has shaped y

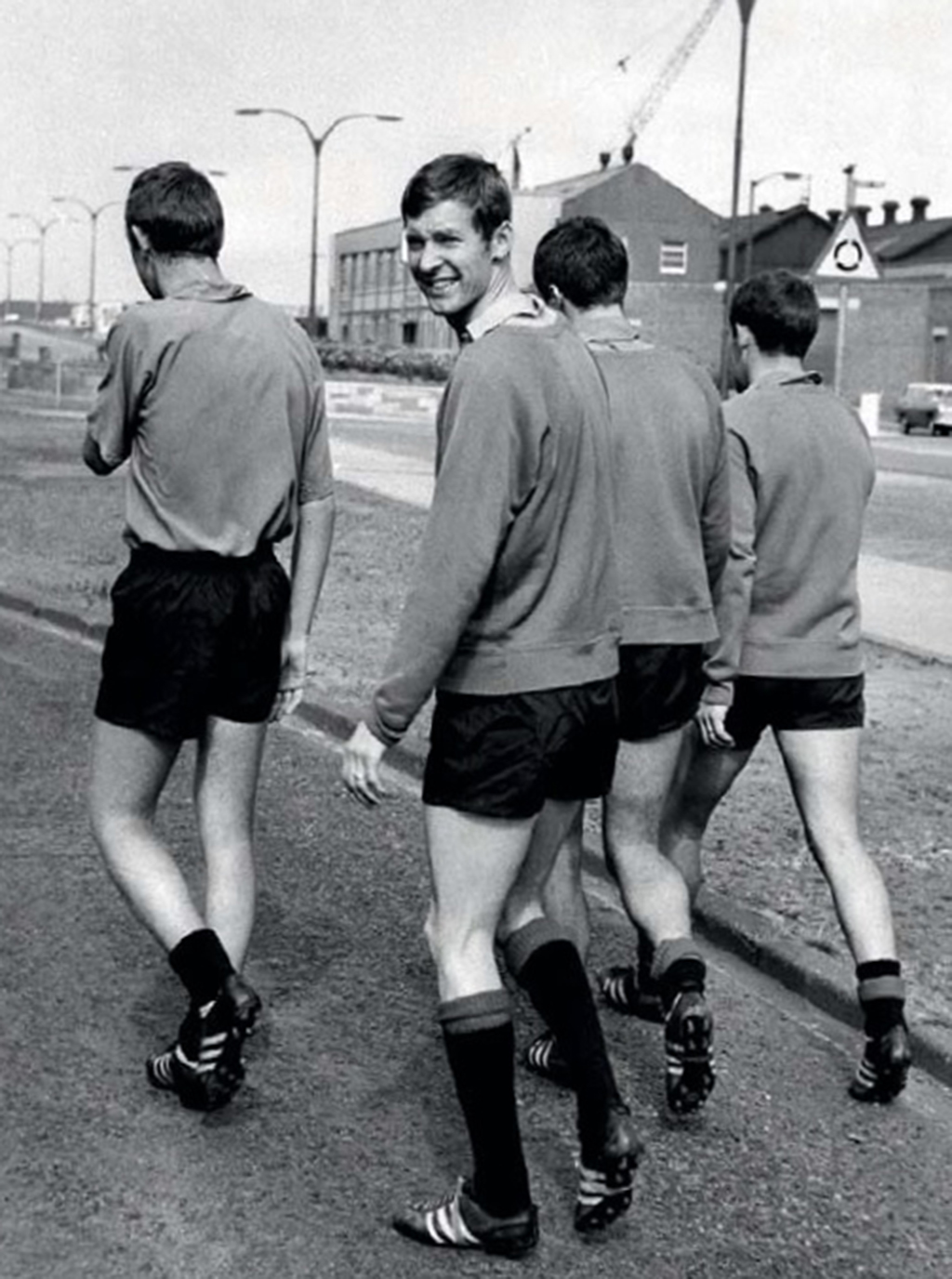

Sir Alex Ferguson, pictured after winning the Champions League with Manchester United

our character?’ and I said ‘do you feel that flipping wind?’

I remember some guy doing an article on me and he said that I’d done well despite coming from Govan. Despite coming from Govan! It’s because I come from Govan that I’ve done well! It gives me something to be proud of: ‘I come from Glasgow’ is a statement.

It’s great to get up early. I’m up early every morning and I’ve got a whole day to enjoy. I try to get it across to my players that working hard is a quality. People think that it’s an easy thing to be able to say ‘he works hard right enough, he’s enthusiastic right enough’ but it’s not. It’s hard to be that way all the time. I love to see guys who are as hard-working now as they were when I first met them.

Glasgow people are very down-to-earth and hard-working. The things that make Glaswegians are the climate, and it was the tobacco and then the shipbuilding.

We were world famous: when people said ‘Clydebuilt’ they meant excellence. We produced some strong men, guys like Jimmy Reid, even the Red Clydesiders like Manny Shinwell and all of these people. James Maxton’s sister was my headmistress at Broomieloan Primary, so there were some great people coming out of Govan. It’s true the working class people became famous fighting for people’s rights, which isn’t something to be ashamed of. On the contrary, it’s something to be proud of.

I came from the sort of community where people reply on each other. If you look at the mining communities where [legendary Scottish football managers] Big Jock [Stein] and Shanks [Bill Shankly] and [Sir Matt] Busby came from they really depended on each other. It’s like that great movie ‘How Green is My Valley’ about the mining disaster in Wales, and that’s what it must have been like in Lanarkshire and Ayrshire. You see these places and all the houses in the miners’ rows all look the same.

Sir Alex retired from management at Old Trafford in 2013

The communities they came from gave them that determination to do well in life, to remember that their loyalty is to each other, and that’s something that all four of us have always had. Shanks was loyal to his club, Stein was loyal to Celtic, Busby was loyal to [Manchester] United. That wasn’t by accident: that’s the sort of human beings they were. They came from a community that depended on loyalty to each other. There was a trust and belief in each other.

In most cases, and particularly in my case, your political views are formed by your parents’ ideology or the way they want to see you brought up. My father was a strong Labour man and my mother was Labour too. I always remember when I was about 25 or 26 and my mother came up to me and said ‘have you voted?’ I said ‘I don’t know how to vote’. She said ‘what do you mean you don’t know how to vote? You get down that school and get your vote! What do you think your father would say?’ That was the very last time I ever dared to mention voting.

My mother was normally quite a quiet woman but she went mad; it was the scorn of her. So I think you’re shaped by your family, although as you get older your personality evolves. But I think my inner instinct is to be a socialist and a Labour man, and no matter how much money I’ve got I will never change that.

Mum was a shop steward at Aero Plastics in Hillington. She was a really big influence on me, as was my dad who was also a shop steward for a time. So that’s always been there. I was a shop steward as an apprentice and led the apprentices’ strike in ‘61 and later on I became the shop steward of the toolroom when I was only 21. The one thing I always felt I had when I was young is that I was always prepared to be decisive.

Whether or not that was an instinct or impulsive, I had it in me to do that, which is why I went on to become a shop steward. There was reason to fi ght for better conditions for the apprentices across the whole of Scotland even though the company I worked for was an American company and we were at a level above, maybe getting five shillings more an hour. But it was about those other apprentices.

If you remember back to those days people got married much younger, many in their teens, so lots of the apprentices were married with kids. It was a different culture and mentality, and most wives didn’t work; their job was to look after the house, bring the kids up, make the dinner in time for their husband coming home, simple as that. So it was a one-wage house in most cases, which was why I felt a responsibility to look after their interests.

This interview was originally published in 2011.

TAGS