Soaring ambition of zoologist who won’t be forgotten

Wildlife activist and zoologist Bryan Nelson devoted his life to studying seabirds in Scotland and beyond, becoming a world expert on gannets and a leading environmentalist.

Seen from outer space, the Bass Rock is said to look extraordinary: shining a brilliant white thanks to being plastered with the guano of generations of gannets and, for most of the year, aglow with the sheer luminosity of the island’s occupants them selves.

This plug of volcanic rock in the Firth of Forth, 350ft tall and just seven acres across, is a hostile environment, continuously battered by the elements – hardly the place, in other words, that one might choose as a honeymoon destination.

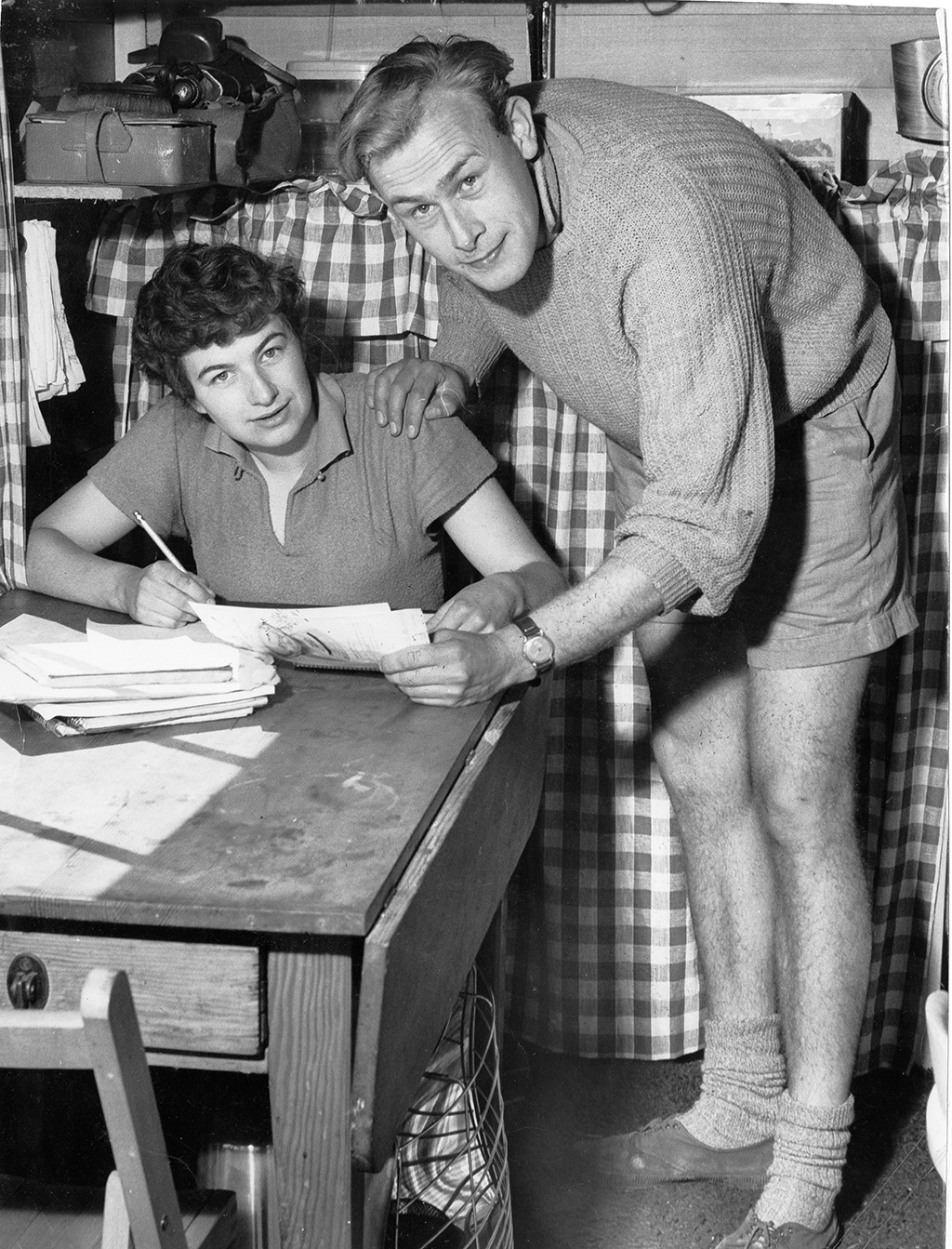

But it was here that Bryan Nelson, the man who was to become the world expert on the North Atlantic gannet, brought his new bride, June, and thus began an incredible partnership that was to endure happily until his death earlier this year. Living in a rough shed amid the ruins of the ancient St Baldred’s chapel, the Nelsons’ first home had to be battened down with rope and tackle.

The intrepid pair arrived on the island in 1960 to research the ecology and behaviour of the gannet, and stayed on the Rock for most of the next three years, surrounded by thousands of birds, accompanied always by their uproarious clamour and pungent aroma.

Lectures at the Scottish Seabird Centre, of which Nelson was a trustee, were always popular

There were earwigs too, which moved in en masse to the cooking pots. And bitter cold, for the hut had neither insulation nor heating.

‘We haven’t yet fallen off the cliffs, though on occasion we deserved to,’ recalled Nelson in his book, Living with Seabirds. ‘I shudder not at my careless disregard of elemen tary precautions, born of a mixture of laziness and perhaps a psychological need to create minor crises for the reward of overcoming them. But fieldwork in lonely and difficult places can be hazardous.’

Nelson was a man with encyclopedic knowledge on most wildlife matters. He cared deeply about what mankind was doing to the environment and the problems facing our hope lessly over-populated planet. But he would always say that rather than letting ourselves get depressed, we should do something about it.

With his aura of an old-fashioned environmentalist and free spirit, he instilled humour and enthusiasm in all who spent time in his company. He was also a man with a great ability to laugh at himself and often related the tale of his and June’s sojourn on a remote Galapagos island, where they were studying booby and frigate birds. Here conditions were, if anything, even more hostile than those on Bass Rock.

They had no fresh water and battled with intense heat, often being obliged to spend their days naked. The Duke of Edinburgh had heard about the couple of incredible researchers living on the remote island and was keen to visit when in the area on the royal yacht Britannia. ‘However egalitarian one may be, one cannot pretend that there is no difference between the Duke of Edinburgh and Joe Bloggs,’ wrote Nelson.

Research took ornithologist Bryan Nelson around the world

He and June were spontaneously invited aboard for lunch. ‘June looked all right, but I took my seat in the dining room, along with the admirals, in bare feet and patched and ragged shorts covered with albatross vomit. It was not unlike the archetypal dream in which one walks along a crowded street with nothing on.’ The Nelsons were both great fans of Prince Philip and Prince Charles, feeling that both cared deeply about conservation matters and were impressively proactive.

While he had lectured at Aberdeen University for many years and was hugely respected for his definitive work The Gannet, Nelson never talked down to those who knew less – everyone, in other words, for he really was the world expert when it came to his beloved solan goose, a very large white gannet with black wing tips.

Nelson’s colourful and valuable career stemmed from his huge passion for birds. From an early age he recognised most of the calls of our common British species. His love for wildlife was enhanced by studying zoology at St Andrews University. Later, following valuable research on blackbirds in Wytham woods in Oxfordshire, he wrote: ‘Had I never seen the guillemots of the Farne Islands, Ailsa’s gannets, Rhum’s shearwaters returning to their burrows on the dark night slopes of Hallival, sobbing so weirdly that the scalp prickled, I might have been content with the blackbirds of Wytham woods.’ He was ever grateful to the Bass Rock’s owner, Hew Hamilton-Dalrymple, for giving him and June permission to work on the island for so long.

One of his greatest achievements was on the other side of the world, where he successfully persuaded the Australian government to designate Christmas Island a National Park, where the rare Abbot’s booby was under threat from the prospect of phosphate mining.

Bryan Nelson with his wife and fellow researcher June in their shed on the Bass Rock

A key player in the establishment of the highly successful Scottish Seabird Centre at North Berwick, Nelson was awarded an MBE for his services to seabirds in 2006. When he retired from his role as trustee of the centre, he com mented: ‘One of the highlights of my time as a trustee has been watching the stupendous growth of the Bass Rock’s gannet colony; it is now the world’s largest Northern gannetry.

When I started in 1960, the colony was confined to the cliffs and now the whole rock is plastered with gannets. It is a wonderful place and the fascinating behaviour of the gannets can be watched on the centre’s live interactive cameras.

‘I once calculated roughly how many thousands of hours I have spent watching gannets on the Bass. I don’t consider any of them to have been wasted. It is said that people come to resemble the animals they identify with. That would make me, like the gannet, handsome, strong, an indomitable fighter and a faithful and long-lived mate.’

With Bryan Nelson’s death at the age of 83 in 2015, we lost one of the world’s finest scientist-field naturalists, a wildlife activist, and a man whose like we will never see again. And always by his side on every step of an incredible global journey studying gannets, booby birds and albatrosses was his lovely wife June. ‘We must work continuously to change this awful attitude that 90 per cent of humans feel no responsibility towards the environment.’

TAGS