Think of the heyday of the Clyde and what names are conjured?

John Brown, Denny, Lithgow, Fairfield, Yarrow and Napier were amongst the shipbuilding titans of a river upon which, in 1914, one quarter of all powered vessels in the world had been launched.

But this year also marks the 115th anniversary of the death of a Glasgow man whose immense contribution to another branch of autical design and construction – the yacht – has only lately begun to be restored to its proper place in the pantheon. George Lennox Watson was as quintessentially a product of his time and birthplace as his fellow Glaswegians, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson and Thomas Lipton.

Watson was later dubbed ‘the Mackintosh of yacht design’ after making a personal fortune from creating supremely elegant vessels for the likes of Lipton, the tea baron who was obsessed with challenges for the sport’s supreme prize, the America’s Cup.

Watson created a staggering 450 designs – today’s equivalent to a launch every three and a half weeks – in a career that ended in his untimely death from heart disease. In pursuit of his evolving ideal marriage of art and science, Watson worked himself into the ground – or perhaps more accurately, the sea.

When he died at the age of 53, he had designed and overseen the construction of yachts for the royalty of Britain, Germany, Austria, Russia, Italy and Belgium, as well as for a roster of industrial and commercial magnates.

George Lennox Watson at the age of 21 (Photo: Martin Black Collection)

Certainly, Watson had been born at exactly the right moment to take advantage of Britain’s primacy as a maritime trading nation.

Watson was born on 31 October, 1851, in the family home at 91 West Regent Street, in an area favoured by the comfortable and prosperous, such as his father, Dr Thomas Watson, an accomplished physician.

After studying at Glasgow High School – and in the year his father died of heart disease aged 52 – George signed on as an apprentice at Napier’s shipyard before crossing the river to the Inglis yard to complete his apprenticeship.

While training alongside John Inglis Jr, Watson became attracted to yachts – his companion was a member of the Royal Clyde Yacht Club – and also acquired the conviction that scientific principles could be applied to their design. In 1871 he designed his first yacht, Peg Woffington, with a greater beam than usual, shallow body and light displacement.

It was a failure because of the incompatibility of an American style of hull with British rigging. But Watson had begun to grasp crucial facts – one example being that bow waves acted as a brake and should be reduced. At the time, it was observed, but not understood, that longer boats travelled faster than shorter vessels.

For a detailed and entertaining account of Watson’s advances in the field, there is no better source than GL Watson – The Art And Science of Yacht Design by Martin Black, which also has many sumptuous photographs of Watson’s creations, the best of which would draw awed crowds to the Clyde if launched today.

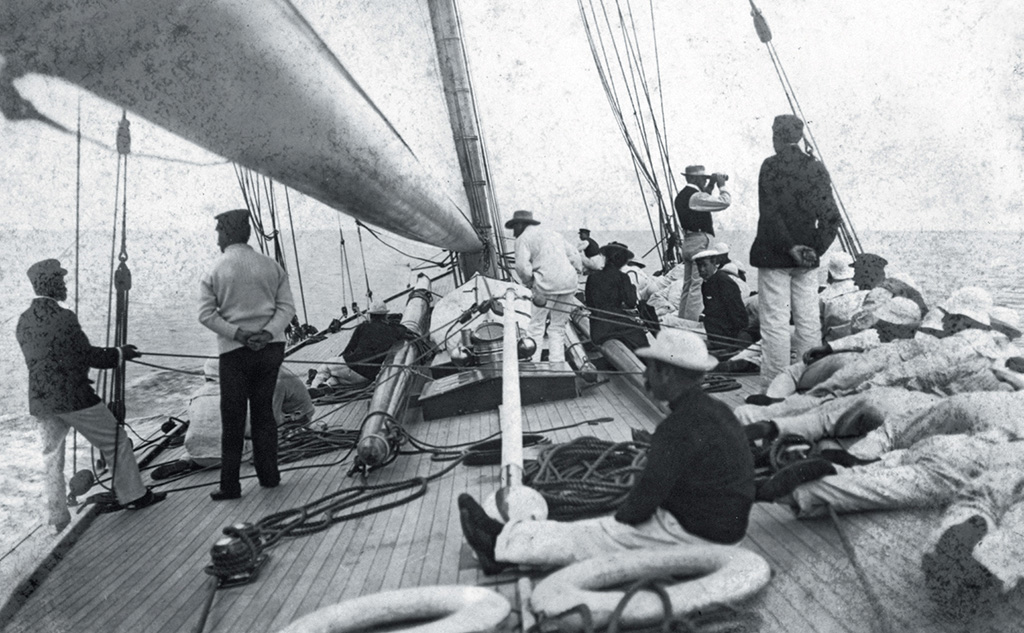

Watson raises his binoculars to spy on the competition during an America’s Cup race (Photo: Martin Black Collection)

By the time he turned 21, Watson was confident he could offer a design service that would suit smaller boats built at smaller yards. It was a bold step but a gamble. The gap in the market was diminutive. In the 1872 season, only 192 yachts competed on the Clyde for a meagre prize pot of £9,712.

In 1875, he received a commission to design and build Clotilde, a five-tonner for racing in Dublin Bay. At the time, another five-ton yacht, Pearl, was the pride of the Clyde, built by the legendary yacht-making dynasty, Fife of Fairlie. Pearl won 16 consecutive Clyde races. Then it came up against Clotilde. They raced from Largs to Rothesay. Clotilde won. They contested the Millport Regatta. Clotilde won. Pearl was withdrawn from the third scheduled race to avoid embarrassment.

George Lennox Watson had launched. He took to his new career with alacrity and a flair for disinformation and news management that would have qualified him as a Downing Street spin doctor nowadays. And it was needed – by the 1890s, when Watson embarked on designing America’s Cup challengers, there were nine full-time correspondents covering Clyde yachting for the newspapers and a similarly voracious sailing press corps in New York and Boston.

The Vril had special significance for Watson who named his house after the vessel (Photo: Martin Black Collection)

He built one of his America’s Cup contenders, Thistle, in a closed shed but was apparently scooped when the Boston Herald published his drawings – only to discover Watson had left out a previous design to fool its reporter.

His career accelerated. The Kaiser placed an order for ‘the fastest yacht in the world’ but Watson’s most famous design was commissioned by Edward, Prince of Wales – Britannia – which remains the most successful racing yacht ever, over a 43-year career.

Yet, after his death and as Clyde shipbuilding declined, Watson was almost forgotten. But for an alert passer-by, who spotted archives left on the pavement for the bin men when Watson’s office had a clear-out, most of his tale would have been lost forever.

Thanks to Martin Black, this remarkable chronicle has found a new and appreciative audience. It is a splendid tribute to George Watson, the greatest yacht designer of his era and – in his own extraordinary way – a Clydebuilt buccaneer.

GL Watson – The Art and Craft of Yacht Design, by Martin Black, RRP €89, www.peggybawnpress.com.

TAGS